Lipoedema – diagnosis, treatment, and experiences

A systematic review and assessment of medical, economic and ethical aspects

Conclusions

- No scientific studies assessing tests to diagnose lipoedema, or methods to distinguish between lipoedema and other conditions were identified.

- There is a lack of scientific studies, with an acceptable risk of bias, assessing methods to treat or cure lipoedema.

- No scientific studies exploring the perceptions or experiences of people living with lipoedema, nor of healthcare professionals who care for people with lipoedema were identified.

- There is insufficient scientific evidence to support a full health economic evaluation.

Internationally accepted diagnostic criteria should be considered as a reference standard in future studies investigating methods to diagnose lipoedema. Such studies are needed to assess the diagnostic accuracy of such methods.

Controlled clinical trials are needed to assess the effects of methods for the treatment of lipoedema. These future studies should, for example, clearly describe the study participants, report why participants are lost to follow-up and use standardized outcome measures. Studies into the perceptions and experiences of those living with lipoedema and the healthcare personnel who care for them are also required.

From an ethical perspective, there is a risk for healthcare inequity and infringements on autonomy. The lack of scientific evidence can lead to a situation where people with lipoedema are not recognized by the healthcare system and do not receive adequate healthcare.

Background

SBU has assessed the scientific base with respect to the diagnosis and treatment of lipoedema at the behest of the Swedish Government (S2019/05315/RS).

There are no known tests or internationally accepted diagnostic criteria for lipoedema. The Swedish diagnostic code for lipoedema is R60.OB. A diagnosis of lipoedema is made based on a combination of the person’s medical history, their symptoms and a clinical examination, as well as by ruling out other conditions with similar symptoms such as lymphoedema, Dercum’s disease, and obesity (BMI>30). Lipoedema is distinguished by the symmetrical accumulation of fat on the hips, thighs, lower legs and or arms that does not involve the hands or the feet. The condition is characterized by pain and sensitivity to pressure in the affected tissues.

There is currently no known cure for lipoedema. Interventions are therefore primarily aimed at relieving symptoms or at reducing functional limitations. Available treatments include diet and exercise advice, compression treatments, and liposuction.

Aim

The aim of this report is to assess the scientific evidence with respect to the diagnosis and treatment of lipoedema, experiences and perceptions of those who have lipoedema regarding their care and support when interacting with healthcare, health economics, and ethical aspects.

Method

A systematic review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA statement (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) and SBU's handbook. The certainty of evidence was assessed with GRADE (http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org).

Inclusion criteria

Diagnosis

Population: Persons with suspected lipoedema

Index test: Method to diagnose or detect lipoedema

Reference test: Internationally accepted diagnostic criteria used to detect lipoedema

Outcome: Diagnostic accuracy

Study design: Randomized controlled trials (RCT) and cross-sectional studies

Study size: At least 10 persons

Language: Swedish, English, Danish and Norwegian

Treatment

Population: Persons with lipoedema. No limitations regarding age or comorbidities

Interventions:

- Change in lifestyle including exercise, change in diet and weight loss

- Intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC), low-frequency vibrotherapy

- Manuel lymph drainage

- Self-care including moisturizing cream or the above mentioned intervention performed by the patient itself

- Liposuction

- Bariatric surgery

- Other interventions aiming to treat lipoedema or alleviate symptoms

Control:

- Placebo

- No treatment

- Waiting list

- Other treatment than the intervention

Outcome:

Primary:

- Pain

- Sensitivity to pressure

- Function including self-assessed capability

- Quality of life

- Bruising

- Side effects of an intervention or control treatment

Secondary:

- Volume

- Swelling

- Motivation

Study design: RCT and controlled clinical trials (CCT). If no other study design is identified, case studies measuring an outcome before or after treatment are included.

Follow-up time: No limitation

Study size: At least 10 persons

Language: Swedish, English, Danish and Norwegian

Experiences

Setting: No limitation

Perspective: A person with lipoedema or a health professional treating a person with lipoedema. No limitations regarding age or comorbidities

Evaluate:

Experience regarding:

- living with lipoedema

- receiving a treatment

- caring for someone with lipoedema

Study design: Qualitative studies or mixed-method studies

Follow-up time: No limitation

Study size: At least 10 persons

Language: Swedish, English, Danish and Norwegian

Search period: Final search March 2021. No limitation regarding year of publication

Databases searched: CINAHL (EBSCO), Cochrane Library (Wiley), EMBASE (Embase.com), Medline (Ovid) and Scopus (Elsevier)

Client/patient involvement: No

Results

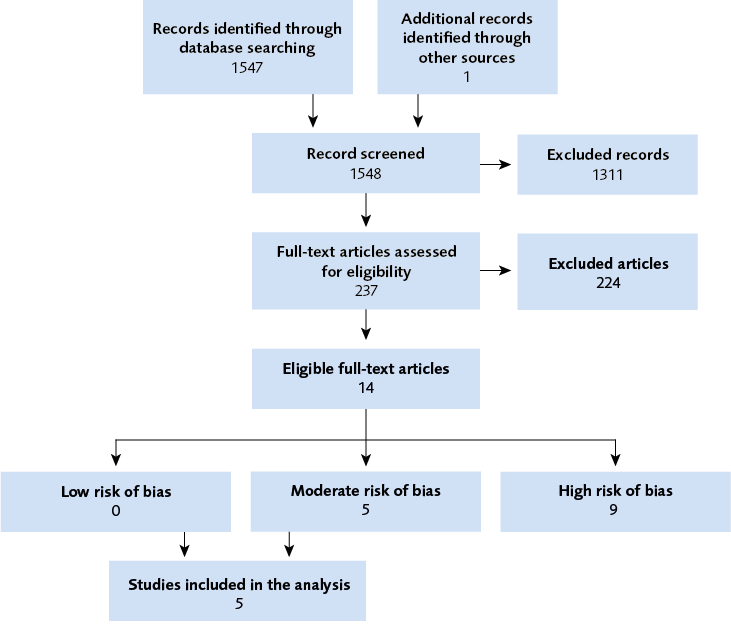

After a systematic literature search and assessment of the retrieved studies, no scientific study assessing a method to diagnose lipoedema was found. Fourteen studies assessing treatments for lipoedema were identified, but none of the studies were judged to be sufficient to inform practice. Five studies with few participants and a moderate risk of bias studied the effects of non-surgical treatments such as manual lymph drainage, physical activity, and diet.

Eight studies with high risk of bias studied the effect of liposuction of affected tissues and one study with high risk of bias studied the effect of bariatric surgery. None of the studies had included a control group. Instead, they had studied or interviewed patients before and after liposuction or bariatric surgery. These studies were evaluated to have a high risk of bias because of risks in participant selection, because participants were not well enough described, because it is difficult to blind studies of liposuction, as well as insufficient reporting of why some people were lost to follow-up. In addition, the results, that are based on patients’ symptoms before and after, are presented at the group level rather than individually. Adverse events were reported in seven of the studies. The most common reported adverse event was post-operative bruising.

There are no qualitative studies that explore experiences and perceptions of living with lipoedema. Neither are there any studies that explore how healthcare providers experience or perceive caring for people with lipoedema.

Cost-effectiveness was not assessed due to lack of scientific evidence from studies with sufficiently low risk of bias for any outcome or method.

The ethical discussion focused on the lack of evidence for the diagnosis and treatment of lipoedema. The situation may lead to both underdiagnosis and misdiagnosis, and that the time between when a person’s first initiates contact with healthcare and when a correct diagnosis is established may take an unreasonably long time. This delay increases the risk that lipoedema may negatively affect the persons quality of life and may allow time for the condition deteriorate, so that they experience more pain and more physical limitations. Which in turn may increase the negative impact lipoedema can have on the person’s ability to have an adequate work- or private life (e. g. parenthood).

The full report in Swedish

Project group

Experts

- Lars Andersson, Senior Lecturer, Marie Cederschiöld University

- Catharina Melander, Senior Lecturer, Luleå University of Technology

- Malin Olsson, Docent, Marie Cederschiöld University and associate professor, Luleå University of Technology

- Leif Perbeck, Docent, Karolinska Institutet

SBU

- Helena Domeij (Project Manager)

- Rebecca Silverstein (Assistant Project Manager from August 2020)

- Frida Mowafi (Assistant Project Manager to August 2020)

- Johanna Wiss (Health Economist to January 2020)

- Anneth Syversson (Project Administrator to april 2021)

- Anna Attergren Granath (Project Administrator from april 2021)

- Ann Kristine Jonsson (Information Specialist)

Scientific reviewers

- Håkan Brorson, MD, adjunct professor, Lund University

- Olafur Jakobsson, MD, PhD.

- Sue Mellgrim, Registred nurse, Lymph therapist, Lymfterapi Norrort, Stockholm

Flow charts of included studies

Figure 1 Flow chart.

Appendices

Reference list of the full report

- Wold LE, Hines EA, Jr., Allen EV. Lipedema of the legs; a syndrome characterized by fat legs and edema. Ann Intern Med 1951;34:1243-50.

- Halk AB, Damstra RJ. First Dutch guidelines on lipedema using the international classification of functioning, disability and health. Phlebology 2017;32:152-9.

- Reich-Schupke S, Schmeller W, Brauer WJ, Cornely ME, Faerber G, Ludwig M, et al. S1 guidelines: Lipedema. Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft 2017;15:758-67.

- Wounds. Best Practice Guidelines: The Management of Lipoedema, [accessed April 21 2021] Available from: https://www.lipoedema.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/WUK_Lipoedema-BPS_Web.pdf. In. Wounds UK, London; 2017.

- Child AH, Gordon KD, Sharpe P, Brice G, Ostergaard P, Jeffery S, et al. Lipedema: an inherited condition. American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part A 2010;152:970-6.

- Dudek JE, Bialaszek W, Ostaszewski P, Smidt T. Depression and appearance-related distress in functioning with lipedema. Psychology Health & Medicine 2018;23:846-53.

- Romeijn JRM, de Rooij MJM, Janssen L, Martens H. Exploration of Patient Characteristics and Quality of Life in Patients with Lipoedema Using a Survey. Dermatology And Therapy 2018;8:303-11.

- Harwood CA, Bull RH, Evans J, Mortimer PS. Lymphatic and venous function in lipoedema. British Journal of Dermatology 1996;134:1-6.

- Bauer AT, von Lukowicz D, Lossagk K, Aitzetmueller M, Moog P, Cerny M, et al. New Insights on Lipedema: The Enigmatic Disease of the Peripheral Fat. Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery 2019;144:1475-84.

- Crescenzi R, Marton A, Donahue PMC, Mahany HB, Lants SK, Wang P, et al. Tissue Sodium Content is Elevated in the Skin and Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue in Women with Lipedema. Obesity 2018;26:310-7.

- Ghods M, Georgiou I, Schmidt J, Kruppa P. Disease progression and comorbidities in lipedema patients: A 10-year retrospective analysis. Dermatologic Therapy 2020;33:e14534.

- Beltran K, Herbst KL. Differentiating lipedema and Dercum's disease. International Journal of Obesity 2017;41:240-5.

- Iker E, Mayfield CK, Gould DJ, Patel KM. Characterizing Lower Extremity Lymphedema and Lipedema with Cutaneous Ultrasonography and an Objective Computer-Assisted Measurement of Dermal Echogenicity. Lymphatic Research & Biology 2019;17:525-30.

- Al-Ghadban S, Cromer W, Allen M, Ussery C, Badowski M, Harris D, et al. Dilated Blood and Lymphatic Microvessels, Angiogenesis, Increased Macrophages, and Adipocyte Hypertrophy in Lipedema Thigh Skin and Fat Tissue. Journal of Obesity 2019;2019:8747461.

- Crescenzi R, Donahue PMC, Petersen KJ, Garza M, Patel N, Lee C, et al. Upper and Lower Extremity Measurement of Tissue Sodium and Fat Content in Patients with Lipedema. 2020;1:907-15.

- Dadras M, Mallinger PJ, Corterier CC, Theodosiadi S, Ghods M. Liposuction in the Treatment of Lipedema: A Longitudinal Study. Archives of Plastic Surgery 2017;44:324-31.

- Rapprich S, Dingler A, Podda M. Liposuction is an effective treatment for lipedema-results of a study with 25 patients. Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft 2011;9:33-40.

- Baumgartner A, Hueppe M, Schmeller W. Long-term benefit of liposuction in patients with lipoedema: a follow-up study after an average of 4 and 8 years. British Journal of Dermatology 2016;174:1061-7.

- Wollina U, Heinig B. Treatment of lipedema by low-volume micro-cannular liposuction in tumescent anesthesia: Results in 111 patients. Dermatologic Therapy 2019;32:e12820.

- Rapprich S, Baum S, Kaak I, Kottmann T, Podda M. Treatment of lipoedema using liposuction: Results of our own surveys. Phlebologie 2015;44:121-32.

- Schmeller W, Hueppe M, Meier-Vollrath I. Tumescent liposuction in lipoedema yields good long-term results. British Journal of Dermatology 2012;166:161-8.

- Szolnoky G, Nagy N, Kovacs RK, Dosa-Racz E, Szabo A, Barsony K, et al. Complex decongestive physiotherapy decreases capillary fragility in lipedema. Lymphology 2008;41:161-6.

- Szolnoky G, Ifeoluwa A, Tuczai M, Varga E, Varga M, Dosa-Racz E, et al. Measurement of capillary fragility: a useful tool to differentiate lipedema from obesity? Lymphology 2017;50:203-9.

- Naouri M, Samimi M, Atlan M, Perrodeau E, Vallin C, Zakine G, et al. High-resolution cutaneous ultrasonography to differentiate lipoedema from lymphoedema. British Journal of Dermatology 2010;163:296-301.

- Herbst KL. Rare adipose disorders (RADs) masquerading as obesity. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2012;33:155-72.

- Meier-Vollrath I, Schmeller W. [Lipoedema--current status, new perspectives]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2004;2:181-6.

- WHO. Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic. Report of a WHO Consultation. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000.

- Szolnoky G, Nemes A, Gavaller H, Forster T, Kemeny L. Lipedema is associated with increased aortic stiffness. Lymphology 2012;45:71-9.

- Wollina U, Heinig B. Tumescent microcannular (laser-asssisted) liposuction in painful lipedema. The European Journal of Aesthetic medicine and Dermatology 2012;2:56-69.

- Dudek J, Białaszek W, Ostaszewski P, Dudek JE, Białaszek W, Ostaszewski P. Quality of life in women with lipoedema: a contextual behavioral approach. Quality of Life Research 2016;25:401-8.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. . PLoS Medicine 2009;6(7).

- SBU. Utvärdering av metoder i hälso- och sjukvården och insatser i socialtjänsten (april 2020). Publicerades endast elektroniskt. 2020.

- Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2016;5:210.

- Baumgartner A, Hueppe M, Meier-Vollrath I, Schmeller W. Improvements in patients with lipedema 4, 8 and 12 years after liposuction. 2021;1:152-9.

- Witte T, Dadras M, Heck FC, Heck M, Habermalz B, Welss S, et al. Water-jet-assisted liposuction for the treatment of lipedema: Standardized treatment protocol and results of 63 patients. 2020;1:1637-44.

- Sanshofer M. HV, Sandhofer M., Sonani Mindt., Moosbauer W., Barsch M. High volume liposuction in tumescence anesthesia in lipedema patients: a retrospective analysis. Journal of Drugs in Dermatology 2021;20.

- Wollina U, Graf A, Hanisch V. Acute pulmonary edema following liposuction due to heart failure and atypical pneumonia. Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift 2015;165:189-94.

- Fink JM, Schreiner L, Marjanovic G, Erbacher G, Seifert GJ, Foeldi M, et al. Leg Volume in Patients with Lipoedema following Bariatric Surgery. Visceral Medicine 2020.

- Szolnoky G, Borsos B, Barsony K, Balogh M, Kemeny L. Complete decongestive physiotherapy with and without pneumatic compression for treatment of lipedema: a pilot study. Lymphology 2008;41:40-4.

- Schneider R. Low-frequency vibrotherapy considerably improves the effectiveness of manual lymphatic drainage (MLD) in patients with lipedema: A two-armed, randomized, controlled pragmatic trial. Physiotherapy Theory & Practice 2020;36:63-70.

- Szolnoky G, Varga E, Varga M, Tuczai M, Dosa-Racz E, Kemeny L. Lymphedema treatment decreases pain intensity in lipedema. Lymphology 2011;44:178-82.

- Di Renzo L, Cinelli G, Romano L, Zomparelli S, Lou De Santis G, Nocerino P, et al. Potential effects of a modified mediterranean diet on body composition in lipoedema. Nutrients 2021;13:1-19.

- Paling I, Macintyre L. Survey of lipoedema symptoms and experience with compression garments. British Journal of Community Nursing 2020;25:S17-S22.

- Metodrådet. Fettsugning som behandling vid lipödem [accessed April 21 2021]. Available from https://cutt.ly/2nzobhm. Sydöstra Sjukvårdsregionen 2020.

- SLL. Fokusrapport 2017:2 Lipödem. In: Stockholm läns landsting, editor., Stockholm; 2017.

- Dudek JE, Bialaszek W, Gabriel M. Quality of life, its factors, and sociodemographic characteristics of Polish women with lipedema. 2021;1:27.

- Nordenfeldt L. The varieties of dignity. Health Care Analysis. 2004;12.

- Toombs SK. The meaning of illness: a phenomenological account of the different perspectives of physician and patient. . Dordrecht, Kluwer Academic.; 1993.

- Beauchamp TJ, F. CJ. Principles of biomedical ethics. New York, NY, Oxford University Press; 2019.

- SMER. ETIK – en introduktion. Stockholm; 2018. isbn 978-91-38-24782-2.

- Rashid M, Kristofferzon M-L, Heiden M, Nilsson A. Factors related to work ability and well-being among women on sick leave due to long-term pain in the neck/shoulders and/or back: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2018;18:672.

- SFS. Hälso- och sjukvårdslag. In: Svensk författningssamling, editor. Elanders Sverige AB, Stockholm; 2017.

- UN. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. In: UN, editor. General Assembly, Geneva; 2015.

- Bräcke. Enkätsvar från Projekt lipödem. Data har erhållits efter kontakt med Christina Ripe vid Bräcke diakoni. Göteborg; 2020.

- Söderberg S, Lundman, B., & Norberg, A. Struggling for dignity: The meaning of women’s experience of living with fibromyalgia. Qualitative Health Research 1999;9:575-87.

- Åsbring P & Närvänen A.-L. Women’s experiences of stigma in relation to chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia. Qualitative Health Research 2002;12:148-60.

Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services

Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook

Share on LinkedIn

Share on LinkedIn

Share via Email

Share via Email