This publication was published more than 5 years ago. The state of knowledge may have changed.

Pharmaceutical treatment in forensic psychiatric care

A systematic review and assessment of the medical, economic, social and ethical aspects

Objective

The conditions when using psychiatric medication differ slightly between forensic and general psychiatry. In this evaluation, SBU describes these differences and investigates their significance on pharmaceutical treatments. The evaluation addresses the benefits, risks and experiences of treatment, in addition to health economics and ethical considerations. The evaluation was made as part of a government assignment.

Conclusions

- Forensic psychiatric care differs from general psychiatric care, both in terms of psychiatric diagnoses and pharmaceutical treatment.

- In forensic psychiatry, it is more common for patients to have been diagnosed with several psychiatric conditions, such as psychosis, autism spectrum disorder, personality disorders and substance use disorders.

- Antipsychotics are administered to most patients in forensic psychiatry, including those who have not been diagnosed with psychosis. In forensic psychiatric care, it is common that patients receive more than one type of antipsychotic. Forensic psychiatric care also tends to administer traditional antipsychotics to a larger extent.

More treatment studies are needed in forensic psychiatry that investigate the effects of pharmaceuticals and if the differences in practice are clinically motivated.

- In addition to the benefits to an individual’s health and safeguarding society, understanding the effects of psychiatric medication also has a major significance on how social resources can be used effectively. Treatment that can shorten the length of forensic psychiatric care and reduce the risk of relapse into crime is most likely cost-effective, especially as the cost of pharmaceuticals is considerably low in relation to the total cost of care.

- Since forensic psychiatric care is conducted under detention, ethical aspects of pharmaceutical treatment are particularly important. One patient and relative association has stated that there is insufficient patient information about medications, which can impede compliance. There is reason to allow for some patient participation, despite their autonomy being restricted to safeguard the public.

- Society has a responsibility to finance research in forensic psychiatry, since the care is involuntary and special consideration must be paid to research ethics. To assess benefits and risks, randomised studies are needed. Thanks to Swedish registers, a strong foundation is available for monitoring effects on important outcomes such as health, length of care and relapse into crime. Patient experiences should also be studied, and the results considered when administering psychiatric care.

Background

In Sweden, a person who has committed a crime under the influence of a severe mental disorder can be sentenced to forensic psychiatric care which is regulated partly by the Health and Medical Services Act and partly by penal law. “Severe mental disorder” is a legal term, not a medical, and the patients in forensic psychiatry are a clinically heterogeneous group. Psychotic disorders are the most common diagnoses, followed by autism spectrum disorder and personality disorders. Virtually all patients are treated with medication. Treatment is often long-term – in some cases lifelong.

Method

The demographics of the patient groups and their pharmaceutical treatments were studied by comparing the Swedish National Forensic Psychiatric Register (RättspsyK) and the National Quality Registry for Psychosis Care (PsykosR) with the National Patient Register and the National Cause of Death Registry.

The evaluation includes systematic reviews of studies in forensic psychiatric care regarding 1) effects of pharmaceutical treatments; 2) the costzeffectiveness of the treatments and 3) patients’ and staff’s experiences of pharmaceutical treatments. We also mapped systematic reviews of pharmaceutical effects on comorbid conditions. To include the perspectives of patients and relatives, we collaborated with the national patients and relative association PAR. We estimated the cost of prescriptions of commonly used medications. Ethical aspects were discussed based on published literature.

Main results

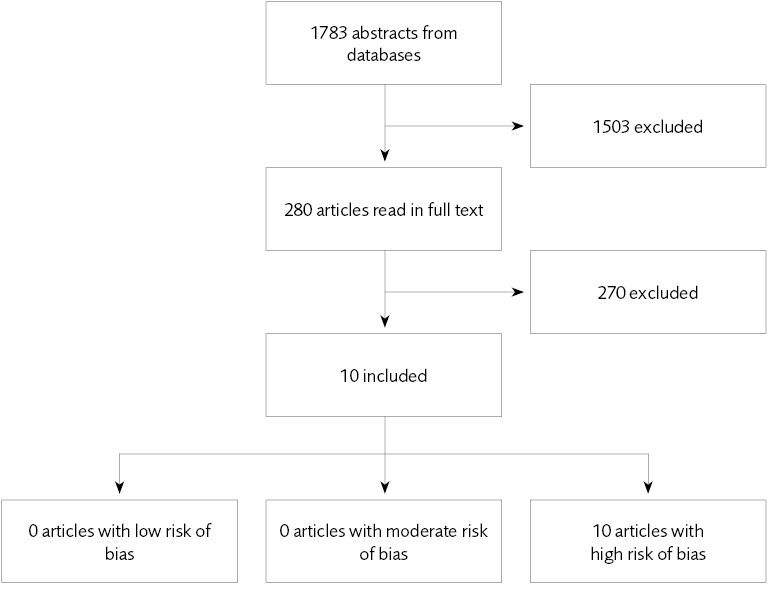

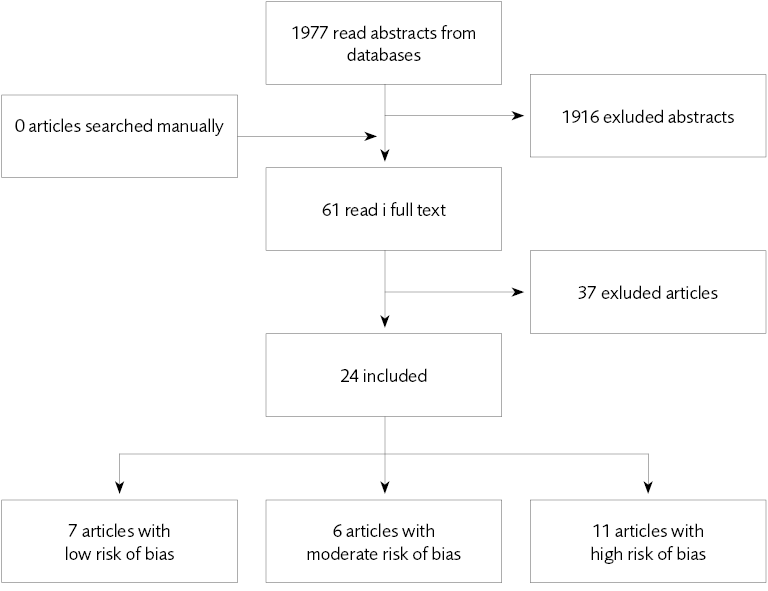

- Benefits and risks. We found ten studies of pharmaceutical treatments used in forensic psychiatry – all with a high risk of bias. These studies were not sufficient for evaluating the benefits and risks of medication used in forensic psychiatric care. In our review of treatments of comorbid conditions, we identified 13 systematic reviews with a low or medium risk of bias. The majority of comorbid conditions lacked systematic reviews.

- Patient groups and pharmaceutical practice. Our register study showed that more patients demonstrate comorbidity with other psychiatric conditions in forensic psychiatry. An assessment of the severity level also indicates more severe psychiatric conditions in forensic psychiatry, particularly among female patients, and a greater risk of premature death (before the age of 50).

Olanzapine is the most prescribed antipsychotic in both general psychiatric psychosis care and forensic psychiatry. Otherwise, traditional antipsychotics are more common in forensic psychiatry. Medication for treatment of ADHD and substance use is also more common among these patients with psychosis, as is anticholinergics to counteract side effects. The use of benzodiazepines in forensic psychiatry has decreased.

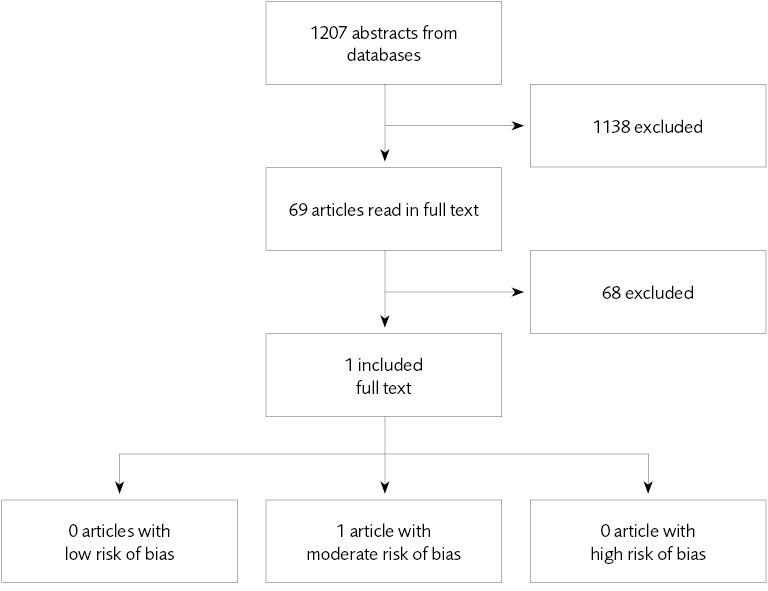

- Experiences. We only found one study that investigated the patients’ own experiences of pharmaceutical treatments in forensic psychiatry. Increased knowledge could lead to changes in the way patients are approached and treatments administered. PAR highlights the need for a dialogue on the selection of medications, a more open discussion of side effects and increased opportunity for other treatments besides pharmaceuticals.

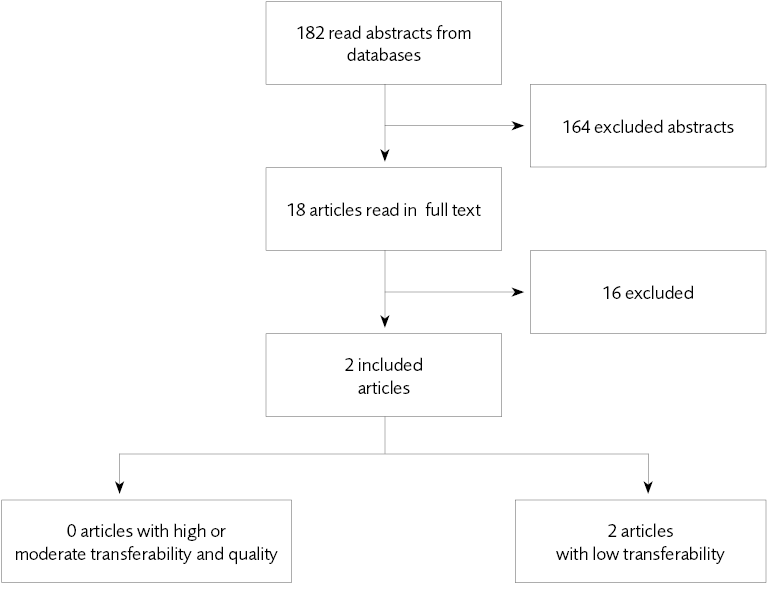

- Health economic aspects. We have been unable to assess the cost-effectiveness of the psychiatric medication included in the report since there is insufficient knowledge of the pharmaceutical effects. In forensic psychiatry, long-acting antipsychotic pharmaceuticals – the most expensive – are often used. However, psychiatric medication forms a very small proportion of the total cost of forensic psychiatric care.

Discussion

Our review of pharmaceutical treatments in forensic psychiatry clearly indicates a neglected area of research. We can also note that forensic psychiatry – like general psychiatry – is limited by the lack of new antipsychotics. Forensic psychiatry would be helped by the development of novel antipsychotics that target the underlying biological causes of psychosis. Development of better treatments is of major significance to both patients and society.

Before new knowledge is achieved, forensic psychiatry should adopt the guidelines that exist for pharmaceutical treatment in general psychiatry. This particularly concerns the national guidelines for treatment with antipsychotics and treatment of substance abuse. Furthermore, it is important that these guidelines are viewed in relation to the special context of care in forensic psychiatry, and that consideration is taken to the comorbid conditions found in forensic psychiatry. Forensic psychiatry has existed for a long time and the experience of various pharmaceutical treatments should be comprehensive. However, this experience needs to be spread throughout forensic psychiatry units to ensure this knowledge is shared.

The full report in Swedish

The full report in Swedish Läkemedelsbehandling inom rättspsykiatrisk vård

Project group

Experts

- Peter Andiné

- Göran Engberg

- Katarina Howner

- Eva Lindström

- Susanna Radovic

SBU

- Monica Hultcrantz (Project Manager)

- Susanne Gustafsson

- Emin Hoxha Ekström

- Caroline Jungner

- Mikael Nilsson

- Hanna Olofsson

- Anna Ringborg

Flow charts

Figure 1 Pharmaceutical studies.

Figure 2 Included studies – pharmacological treatment and psychiatric co-morbidity.

Figure 3 Included studies – experiences and perceptions.

Figure 4 Included studies – health economic studies.

References

- SBU. Behandling och bedömning i rättspsykiatrisk vård. En kartläggning av systematiska översikter. Stockholm: Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering (SBU); 2017. SBU-rapport nr 264. ISBN 978-91-88437-06-8.

- Nationellt rättspsykiatriskt kvalitetsregister (RättspsyK). Årsrapport 2017. Tryckår 2018.

- Socialstyrelsen. Nationella riktlinjer för vård och stöd vid schizofreni och schizofrenilikande tillstånd. Stöd för styrning och ledning. (Remissversion). 2017. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/Lists/Artikelkatalog/Attachments/20735/2017-10-34.pdf

- SBU. Etiska aspekter på åtgärder inom hälso- och sjukvården. Reviderad 2014. Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering (SBU). Tillgänglig från http://www.sbu.se/globalassets/ebm/metodbok/mall_etiska_aspekter.pdf.

- Kartläggning 2016. Rättspsykiatri. En kartläggning gjord av Helseplan Nysam. Uppdrag Psykisk Hälsa, Sveriges Kommuner och Landsting 2017.

- Nilsson T, Wallinius M, Gustavson C, Anckarsater H, Kerekes N. Violent recidivism: a long-time follow-up study of mentally disordered offenders. PLoS One 2011;6:e25768.

- Wolf A, Fanshawe TR, Sariaslan A, Cornish R, Larsson H, Fazel S. Prediction of violent crime on discharge from secure psychiatric hospitals: A clinical prediction rule (FoVOx). Eur Psychiatry 2018;47:88-93.

- Kriminalvården. Kriminalvård och Statistik 2016 (KOS 2016). Tryckår 2017. ISSN 1400-2167. https://www.kriminalvarden.se/globalassets/forskning_statistik/kos-2016-kriminalvard-och-statistik.pdf

- Meltzer HY. What’s atypical about atypical antipsychotic drugs? Curr Opin Pharmacol 2004;4:53-7.

- Meltzer HY. Clozapine: balancing safety with superior antipsychotic efficacy. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses 2012;6:134-44.

- Veerman SRT, Schulte PFJ, de Haan L. Treatment for Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia: A Comprehensive Review. Drugs 2017;77:1423-59.

- Desamericq G, Schurhoff F, Meary A, Szoke A, Macquin-Mavier I, Bachoud-Levi AC, et al. Long-term neurocognitive effects of antipsychotics in schizophrenia: a network meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2014;70:127-34.

- Pompili M, Baldessarini RJ, Forte A, Erbuto D, Serafini G, Fiorillo A, et al. Do Atypical Antipsychotics Have Antisuicidal Effects? A Hypothesis-Generating Overview. Int J Mol Sci 2016;17.

- Remington G, Lee J, Agid O, Takeuchi H, Foussias G, Hahn M, et al. Clozapine’s critical role in treatment resistant schizophrenia: ensuring both safety and use. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2016;15:1193-203.

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924-6.

- Lewin S, Glenton C, Munthe-Kaas H, Carlsen B, Colvin CJ, Gulmezoglu M, et al. Using qualitative evidence in decision making for health and social interventions: an approach to assess confidence in findings from qualitative evidence syntheses (GRADE-CERQual). PLoS Med 2015;12:e1001895.

- HTAi Interest Group on Patient and Citizen Involvement in HTA (PCIG). Patient Group Submission Template for HTA of Medicines. Tillgänglig från https://htai.org/interest-groups/pcig/resources/for-patients-and-patient-groups/. Nedladdad 2016-06-01.

- Socialstyrelsen. Täckningsgrader 2017. Jämförelser mellan nationella kvalitetsregister och hälsodataregistren. Tryckår 2017. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/Lists/Artikelkatalog/Attachments/20794/2017-12-37.pdf

- Balbuena L, Mela M, Wong S, Gu D, Adelugba O, Tempier R. Does clozapine promote employability and reduce offending among mentally disordered offenders? Can J Psychiatry 2010;55:50-6.

- Dalal B, Larkin E, Leese M, Taylor PJ. Clozapine treatment of long-standing schizophrenia and serious violence: A two-year follow-up study of the first 50 patients treated with clozapine in Rampton high security hospital. Crim Behav Ment Health 1999;9:168-78.

- Mela M, Depiang G. Clozapine’s Effect on Recidivism Among Offenders with Mental Disorders. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 2016;44:82-90.

- Stoner SC, Wehner Lea JS, Dubisar BM, Roebuck-Colgan K, Vlach DM. Impact of clozapine versus haloperidol on conditional release time and rates of revocation in a forensic psychiatric population. Journal of Pharmacy Technology 2002;18:182-6.

- Swinton M, Haddock A. Clozapine in special hospital: A retrospective case-control study. J Forens Psychiatry Psychol 2000;11:587-96.

- Beck NC, Greenfield SR, Gotham H, Menditto AA, Stuve P, Hemme CA. Risperidone in the management of violent, treatment-resistant schizophrenics hospitalized in a maximum security forensic facility. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 1997;25:461-8.

- Collins P, Larkin E, Shubsachs A. Lithium carbonate in chronic schizophrenia–a brief trial of lithium carbonate added to neuroleptics for treatment of resistant schizophrenic patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1991;84:150-4.

- Gobbi G, Comai S, Debonnel G. Effects of quetiapine and olanzapine in patients with psychosis and violent behavior: A pilot randomized, open-label, comparative study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2014;10:757-65.

- Gobbi G, Gaudreau PO, Leblanc N. Efficacy of topiramate, valproate, and their combination on aggression/agitation behavior in patients with psychosis. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2006;26:467-73.

- Tavernor R, Swinton M, Tavernor S. High-dose antipsychotic medication in maximum security. J Forens Psychiatry Psychol 2000;11:36-48.

- McLoughlin BC, Pushpa-Rajah JA, Gillies D, Rathbone J, Variend H, Kalakouti E, et al. Cannabis and schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014.

- Sawicka M, Tracy DK. Naltrexone efficacy in treating alcohol-use disorder in individuals with comorbid psychosis: a systematic review. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol 2017;7:211-24.

- Wilson RP, Bhattacharyya S. Antipsychotic efficacy in psychosis with co-morbid cannabis misuse: A systematic review. J Psychopharmacol 2016;30:99-111.

- Arranz B, Garriga M, García-Rizo C, San L. Clozapine use in patients with schizophrenia and a comorbid substance use disorder: A systematic review. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2017.

- Sabioni P, Ramos AC, Galduroz JC. The effectiveness of treatments for cocaine dependence in schizophrenic patients: a systematic review. Curr Neuropharmacol 2013;11:484-90.

- Khushu A, Powney MJ. Haloperidol for long-term aggression in psychosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;11:CD009830.

- Ayub M, Saeed K, Munshi TA, Naeem F. Clozapine for psychotic disorders in adults with intellectual disabilities. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015.

- Huband N, Ferriter M, Nathan R, Jones H. Antiepileptics for aggression and associated impulsivity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010.

- Ingenhoven T, Lafay P, Rinne T, Passchier J, Duivenvoorden H. Effectiveness of pharmacotherapy for severe personality disorders: meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry 2010;71:14-25.

- Ingenhoven TJ, Duivenvoorden HJ. Differential effectiveness of antipsychotics in borderline personality disorder: meta-analyses of placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trials on symptomatic outcome domains. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2011;31:489-96.

- Nosé M, Cipriani A, Biancosino B, Grassi L, Barbui C. Efficacy of pharmacotherapy against core traits of borderline personality disorder: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2006;21:345-53.

- Stoffers J, Völlm BA, Rücker G, Timmer A, Huband N, Lieb K. Pharmacological interventions for borderline personality disorder. In. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Food and Drug Toxicology Research Centre, National Institute of Nutrition, Hyderabad, India. DO - 10.1002/jat.2718 [doi] England; 2010.

- Varghese BS, Rajeev A, Norrish M, Al Khusaiby SBM. Topiramate for anger control: A systematic review. Indian J Pharmacol 2010;42:135-41.

- Tsoi DT, Porwal M, Webster AC. Interventions for smoking cessation and reduction in individuals with schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;2017.

- Mills A, Lathlean J, Bressington D, Forrester A, van Veenhuyzen W, Gray R. Prisoners’ experiences of antipsychotic medication: Influences on adherence. J Forens Psychiatry Psychol 2011;22:110-125.

- Tandvård- och läkemedelsförmånsverket. MEDPrice. Pris- och beslutsdatabasen. https://www.tlv.se/beslut/sok-i-databasen.html

- Kriminalvården. Årsredovisning 2017. https://www.kriminalvarden.se/globalassets/publikationer/ekonomi/kriminalvardens-arsredovisning-2017.pdf

- Brottsförebyggande rådet (BRÅ). Att minska isolering i häkte - Lägesbild och förslag. Rapport 2017:6. ISBN 978-91-87335-83-9.

- Åklagarmyndigheten. Årsredovisning 2017. https://www.aklagare.se/globalassets/dokument/planering-och-uppfoljning/arsredovisningar/arsredovisning-2017.pdf

- Rättsmedicinalverket. Årsredovisning 2017. Dnr X17-90134. https://www.rmv.se/wp-content/uploads/arsredovisning2017-tillganglighetsanpassad.pdf

- Sveriges domstolar. Årsredovisning 2017. http://www.domstol.se/Publikationer/Arsredovisning/arsredovisning_2017_sverigesdomstolar.pdf

- Adshead G. Care or custody? Ethical dilemmas in forensic psychiatry. J Med Ethics 2000;26:302-4.

- Cislo AM, Trestman R. Challenges and solutions for conducting research in correctional settings: the U.S. experience. Int J Law Psychiatry 2013;36:304-10.

- Elliott C, Lamkin M. Restrict the Recruitment of Involuntarily Committed Patients for Psychiatric Research. JAMA Psychiatry 2016;73:317-8.

- Moser DJ, Arndt S, Kanz JE, Benjamin ML, Bayless JD, Reese RL, et al. Coercion and informed consent in research involving prisoners. Compr Psychiatry 2004;45:1-9.

- Adshead G, Davies T. Wise restraints: ethical issues in the coercion of forensic patients. In Völlm B, Nedopil N (red). The use of coercive measures in forensic psychiatric care: Legal, ethical and practical challenges. Springer International Publishing 2016. ISBN 3319267485, 9783319267487.

- World Health Organization. Promoting mental health: Concepts, emerging evidence, practice (Summary report). Geneva; 2004. http://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/en/promoting_mhh.pdf

- David AS. Insight and psychosis. Br J Psychiatry 1990;156:798-808.

- Diesfeld K. Insight: Unpacking the Concept in Mental Health Law. Psychiatr Psychol Law 2003;10:63-70.

- Weisburd D. Ethical practice and evaluation of interventions in crime and justice The moral imperative for randomized trials. Eval Rev 2003:27:336-54.

- Nationellt kvalitetsregister för psykossjukdomar (PsykosR): Årsrapport 2016. Tryckår 2017. Utgivare Ing-Marie Wieselgren.

- Crump C, Winkleby MA, Sundquist K, Sundquist J. Comorbidities and mortality in persons with schizophrenia: a Swedish national cohort study. Am J Psychiatry 2013;170:324-33.

- Taipale H, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Alexanderson K, Majak M, Mehtala J, Hoti F, et al. Antipsychotics and mortality in a nationwide cohort of 29,823 patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2017.

- Tiihonen J, Lonnqvist J, Wahlbeck K, Klaukka T, Niskanen L, Tanskanen A, et al. 11-year follow-up of mortality in patients with schizophrenia: a population-based cohort study (FIN11 study). Lancet 2009;374:620-7.

- Gabor T. Costs of Crime and Criminal Justice Responses. Public Safety Canada 2015;Research report: 2015–R022.

- McCollistera KE, French MT, Fang H. The Cost of Crime to Society: New Crime-Specific Estimates for Policy and Program Evaluation. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010 April 1; 108(1-2): 98–109. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.12.002. 2010.

- Dolan P GL, Peasgood T, Tsuchiya A. Estimating the intangible victim costs of violent crime. Br J Criminol. 2005;(2005) 45, 958-976.

- Socialstyrelsen. Nationella riktlinjer för antipsykotisk läkemedelsbehandling vid schizofreni och schizofreniliknande tillstånd. 2014. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/SiteCollectionDocuments/nr-schizofreni-antipsykotiska-lakemedel-vetenskapligt-underlag.pdf

- Socialstyrelsen. Nationella riktlinjer för vård och stöd vid missbruk och beroende. 2017. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/SiteCollectionDocuments/2017-12-23-vetenskapligt%20underlag.pdf

- SBU. Psykologiska behandlingar och psykosociala insatser i rättspsykiatrisk vård. Systematiska översikter av effektstudier, patientupplevelser och ekonomiska aspekter, samt en etisk analys. Stockholm: Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering (SBU); 2018. SBU-rapport nr 287. ISBN 978-91-88437-29-7.

Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services

Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook

Share on LinkedIn

Share on LinkedIn

Share via Email

Share via Email