This publication was published more than 5 years ago. The state of knowledge may have changed.

Organisational models for securing access to health and dental care services for children in out-of-home care

A systematic review and assessment of medical, economic, social and ethical aspects

Background and aim

Children who enter or reside in out-of-home care are in greater need of health and dental care services than other children.

This report is one in a series of reports where SBU has examined interventions for children in out-of-home care (foster or residential care). The aim is to evaluate organisational models for securing access to health and dental care for children in out-of-home care.

Conclusions

- An investigation of current Swedish practice in local child welfare shows that less than half of the Swedish local authorities have systematic routines to ensure that children in out-of-home care receive assessment of their physical health, only ten percent provide an oral health assessment and no local authority has routines for assessing mental health.

- We did not find any studies of adequate quality, therefore it is not possible to determine the effects of organisational models for providing health and dental care to childrenin out-of-home care. Henceforth, when organisational models are introduced in practice, well-conducted follow-up studies investigating their effects should be performed. There is also a need for studies that assess the prevalence of physical, dental and mental health problems and oral illness among children entering or residing in out-of-home care.

- From an ethical point of view, it is important that children in out-of-home care are provided appropriate health and dental care. The new requirements in the Swedish law (5 kap. 1 d § SoL) regarding mandatory health assessments for children entering out-of-home care should be followed-up and evaluated. There is also a need for establishing organisational models in Swedish practice to ensure that the rights and needs of health and dental care for these individuals are met.

- In an international perspective, promising organisational models that could secure that these individuals receive health and dental care do exist, but they have not been evaluated with sufficient scientific rigour. A cost calculation performed by SBU suggests that an organisational model could be implemented in the Swedish system at a low cost with potential benefits for children in out-of-home care.

What does this report add?

This report shows that children in out-of-home care in Sweden do not receive adequate health and dental care. Furthermore, the report stresses the need for scientific evaluations of organisational models that could secure the access to health and dental care for this vulnerable group. An organisational model inspired by the English health care system is described as an example of how a Swedish organisational model could be designed.

Method

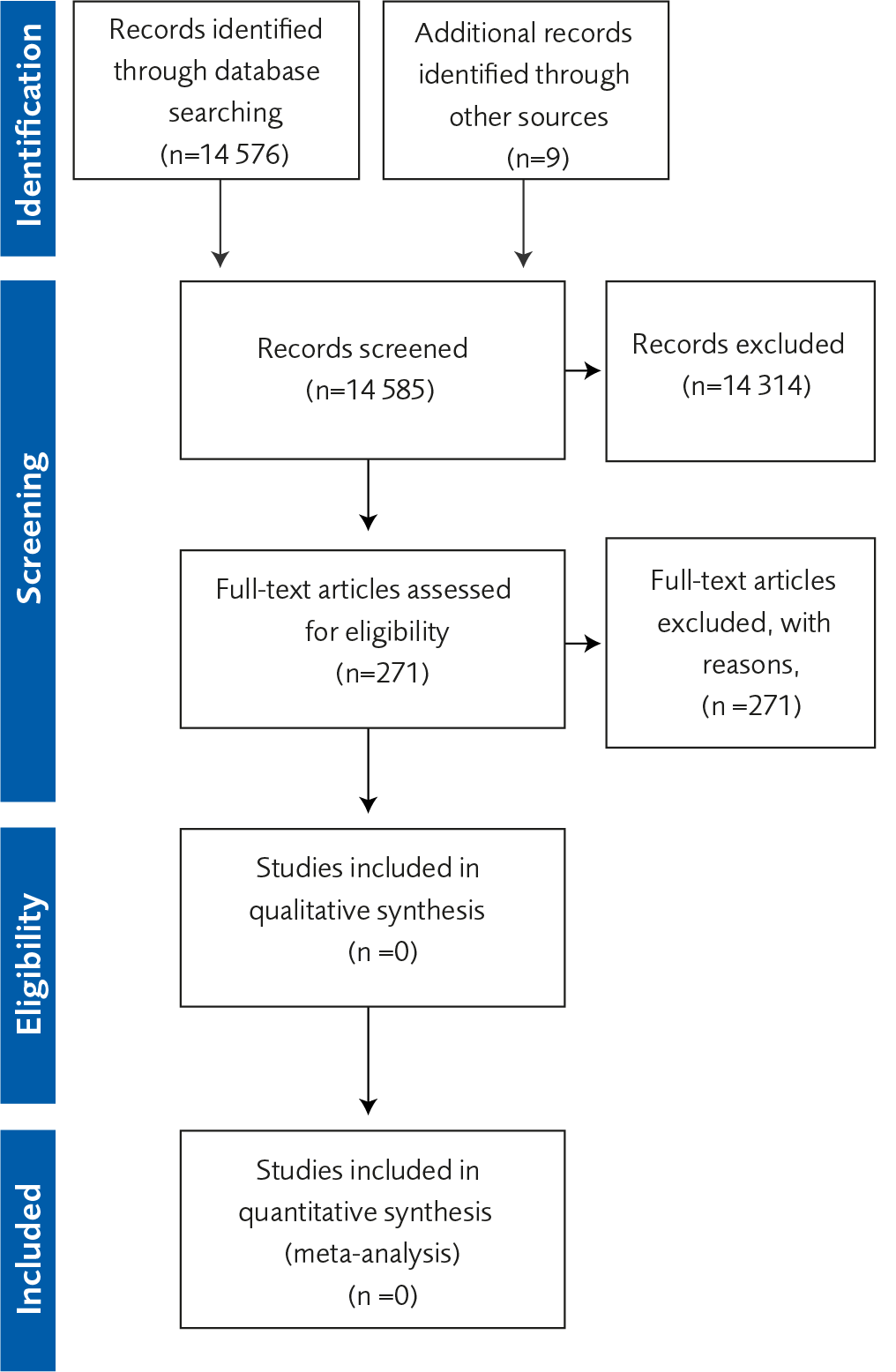

The report includes a systematic review of studies investigating the effects of organisational models aimed to secure access to health and dental care for children in out-of-home care.

In addition, the report contains an investigation of current practice in Sweden of routines and structures through electronic surveys that were followed-up via phone interviews with representatives of local child welfare authorities. Ethical, social and legal questions were also analysed by reviewing relevant literature, governmental reports and legal documents. Finally, an economic evaluation was conducted investigating the resources needed for an organisational model that could secure that children in out-of-home care receive health and dental care.

Main results

Investigation of current practice

In the evaluation of Swedish practice, 106 local authorities received an electronic survey with questions regarding routines and methods used to secure that children entering or residing in out-of-home care are provided with health and dental check-ups. The survey was followed-up with phone interviews. Taken together, the results show that less than half of the Swedish local authorities have systematic routines to ensure that children entering out-of-home care receive assessment of their physical health, only 10% provide an oral health assessment and no local authority has routines for assessing mental health. Furthermore, very few councils secure that these children receive systematic follow-up health assessments while they reside in out-of-home care.

Systematic review

In the systematic review, we did not identify any studies with low or moderate risk of bias that had investigated the effects of an organisational model for securing that children in out-of-home care receive adequate health and dental care.

Ethical, social and legal aspects

Since 2017, local councils have a mandated duty to provide health assessments (physical, dental and mental health) for children entering out-of-home care to acquire health examinations. The new legislation should be followed-up and evaluated. Possible, stricter regulations for implementation of the law need to be introduced.

The costs for a possible organisational model

An organisational model (inspired by the legal framework and implementation in England) to identify physical, mental and dental health problems among children in out-of-home care could imply low costs. The initial cost to set up the model would amount to approximately 5.5 million Swedish kronor (SEK), while the yearly cost per child would be SEK 3 300. This model would most likely lead to an increase in the use of health and dental care services, and thereby probably improve the health of childrenin out-of-home care.

Discussion

Research, policy and practice

SBU proposes a nation-wide follow-up of how the new legislation has been implemented with a focus on whether systematic routines in local practice have been established or not. Furthermore, SBU proposes that the initial phase for establishing an organisational model that secures the access to health and dental care, which includes developing standardised check-lists for health examinations and forming a digital health card, should be led by one central national body. In addition, action plans on a more local level also need to be developed. Although the model should come with low costs, most of the initial financial burden will fall on local councils where the care workers and their supervisors, will need an introductory course in order to systematically implement new routines and protocols. Finally, after the suggested organisational model has been implemented, its use and effects should be followed-up and evaluated.

The full report in Swedish

The full report in Swedish Organisatoriska modeller för att barn och unga i familjehem eller på institution ska få hälso- och sjukvård och tandvård

Project group

Experts

- Anders Hjern, Stockholm University and Karolinska Institutet

- Gunilla Klingberg, Malmö University

- Titti Mattsson, Lund University

- Tita Mensah, Malmö University

- Bo Vinnerljung, Stockholm University and Karolinska Institutet

SBU

- Sofia Tranæus, Project Manager

- Kickan Håkanson, Project Administrator

- Pia Johansson, Health Economist

- Ann Kristine Jonsson, Information Specialist

- Kerstin Mothander, Assistant

- Pernilla Östlund, Assistant Project Administrator

Flow charts

Appendices

References

- SBU. Insatser för bättre psykisk och fysisk hälsa hos familjehemsplacerade barn. Stockholm: Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering (SBU); 2017. SBU-rapport nr 265. ISBN 978-91-88437-07-5.

- Vinnerljung B. Hur vanligt är det att ha varit fosterbarn? En deskriptiv epidemiologisk studie. Socialvetenskaplig Tidskrift 1996;3:166-179.

- Vinnerljung B, Hjern A, Ringbeck Weitoft G, Franzén E, Estrada F. Children and young people at risk. Int J Soc Welf 2007;16:163-202.

- Fallesen P, Emanuel N, Wildeman C. Cumulative risks of foster care placement for Danish children. PloS one 2014;9:e109207.

- Mc Grath-Lone L, Dearden L, Nasim B, Harron K, Gilbert R. Changes in first entry to out-of-home care from 1992 to 2012 among children in England. Child Abuse Negl 2016;51:163-71.

- Eurochild - Children in alternative care - National Surveys - 2nd Edition January 2010, http://eurochild.org.

- Socialstyrelsen. Sociala skillnader i tandhälsa bland barn och unga. Underlagsrapport till Barns och ungas hälsa, vård och omsorg 2013. Artikelnummer: 2013-5-34.

- Wettergren B, Blennow M, Hjern A, Söder O, Ludvigsson JF. Child Health Systems in Sweden. J Pediatr 2016;177S:187-202.

- Schor EL. The foster care system and health status of foster children. Pediatrics 1982;69:521-28.

- Bamford FN, Wohlkind SN. The physical and mental health of children in care: Research needs (two papers), Swindon: ESRC, 1988.

- Chernoff R, Combs-Orme T, Risley-Curtiss C, Heisler A. Assessing the health status of children entering foster care. Pediatrics 1994;93:594-601.

- Haflon N, Mendonca A, Berkowitz G. Health status of children in foster care. The experience of the Center for the vulnerable child. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1995;149:386-92.

- Bundle A. Health of teenagers in residential care: comparison of data held by care staff with data in community child health records. Arch Dis Child 2001;84:10-14.

- Hill C, Thompson M. Mental and physical health co-morbidity in looked-after children. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 2003;8:315-21.

- Hill C, Watkins J. Statutory health assessments for looked-after children: what do they achieve? Child Care Health Dev 2003;29:3-13.

- Anderson L, Vostanis P, Spencer N. The health needs of children aged 6-12 years in foster care. Adoption &Fostering 2004;28:31-40.

- Hansen RL, Mawjee FL, Barton K, Metcalf MB, Joye NR. Comparing the health status of low-income children in and out of foster care. Child Welfare 2004;83:367-80.

- Kristoffersen L. Barnevernbarnas helse. Uførhet og dødelighet i perioden 1990–2002 NIBR-rapport 2005:12. ISBN: 82-7071-564-6.

- Jee SH, Barth RP, Szilagyi MA, Szilagyi PG, Aida M, Davis MM. Factors associated with chronic conditions among children in foster care. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2006;17:328-41.

- Leslie LK, Gordon JN, Meneken L, Premji K, Michelmore KL, Ganger W. The physical, developmental, and mental health needs of young children in child welfare by initial placement type. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2005;26:177-85.

- Miller LC, Chan W, Litvinova A, Rubin A, Tirella L, Cermak S. Medical diagnoses and growth of children residing in Russian orphanages. Acta Paediatr 2007;96:1765-9.

- Nathanson D, Tzioumi D. Health needs of Australian children living in out-of-home care. J Paediatr Child Health 2007;43:695-9.

- Zewdu AM. Health-related benefits among children in the child welfare system: Prevalence and determinants of basic and/or attendance benefits. Norsk Epidemiologi 2010;20:77-84.

- Kaltner M, Rissel K. Health of Australian children in out-of-home care: needs and carer recognition. J Paediatr Child Health 2011;47:122-6.

- Lightfoot E, Hill K, LaLiberte T. Prevalence of children with disabilities in the child welfare system and out of home placement: An examination of administrative records. Child Youth Serv Rev 2011;33:2069-75.

- Schneiderman JU, Leslie LK, Arnold-Clark JS, McDaniel D, Xie B. Pediatric health assessments of young children in child welfare by placement type. Child Abuse Negl 2011;35:28-39.

- Simkiss D. Outcomes for looked after children and young people. Paediatrics and Child Health 2012;22:388-92.

- Stein R, Hurlburt M, Heneghan A, Zhang J, Rolls-Reutz J, Silver E, et al. Chronic conditions among children investigated by child welfare: A national sample. Pediatrics 2013;131:455-62.

- Jaudes P, Bilaver L, Champange V. Do children in foster care receive appropriate treatment for asthma? Child Youth Serv Rev 2015;52:103-09.

- Jaudes P, Weil L, Prior J, Sharp D, Holzberg M, McClelland G. Wellbeing of children and adolescents with special health care needs in the child welfare system. Child Youth Serv Rev 2016;70:276-83.

- Köhler M, Emmelin M, Hjern A, Rosvall M. Children in family foster care have greater health risks and less involvement in Child Health Services. Acta Paediatr 2015;104:508-13.

- Szilagyi M, Rosen D, Rubin D, Zlotnik S. Health care issues for children and adolescents in foster care and kinship care. Pediatrics 2015;136:1142-166.

- Tanguy M, Rousseau D, Duverger P, Nguyen S, Fanello S. Parcours et devenir de 128 enfants admis avant l’age de quatre ans en pouponniere sociale [Course and progression of children admitted before 4 years of age in a French welfare center]. Archives de Pediatrie 2015;22:1129-39.

- Kling S, Vinnerljung B, Hjern A. Somatic assessments of 120 Swedish children taken into care reveal large unmet health and dental care needs. Acta Paediatr 2016;105:416-20.

- Kling S, Vinnerljung B, Hjern A. Hälsokontroll för SiS-ungdomar. En studie av hälsoproblem och vårdbehov hos ungdomar på fyra särskilda ungdomshem. Institutionsvård i Fokus. Rapportnummer: 4, 2016. ISBN: 978-91-87053-40-5.

- Turney K, Wildeman C. Mental and physical health of children in foster care. Pediatrics 2016;138:e20161118.

- Dunnigan A, Thompson T, Jonson-Reid M, Drake B. Chronic health conditions and children in foster care: Determining demographic and placement-related correlates. J Public Child Welfare 2017;11:586-598.

- Randsalu LS, Laurell L. Children in out-of-home care are at high risk of somatic, dental and mental ill health. Acta Paediatr 2018;107:301-06.

- Aguilia A, Gonzalez-Garcia C, Bravo A, Lazaro-Visa S, del valle J (submitted). Children and young people with intellectual disabilities in residential care. Prevalence of mental health disorders and therapeutic interventions.

- Viner R, Taylor B. Adult health and social outcomes of children who have been in public care: Population-based study. Pediatrics 2005;115:894-99.

- Vinnerljung B, Brännström L, Hjern A. Disability pension among adult former child welfare clients: A Swedish national cohort study. Child Youth Serv Rev 2015;56:169-76.

- Kessler R, Pecora P, Williams J, Hiripi E, O’Brian K, English D, et al. Effects of enhanced foster care on the long-term physical and mental of foster care alumni. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2008;65:625-33.

- Vinnerljung B, Sallnäs M. Into adulthood: a follow-up study of 718 young people who were placed in out-of-home care during their teens. J Child Fam Soc Work 2008;13:144-55.

- Schneider R, Baumrid N, Pavao J, Stockdale G, Castelli P. What happens to youth removed from parental care? Health and economic outcomes for women with a history of out-of-home placement. Child Youth Serv Rev 2009;31:440-44.

- Berlin M, Vinnerljung B, Hjern A. School performance in primary school and psychosocial problems in young adulthood among care leavers from long term foster care. Child Youth Serv Rev 2011;33:2489-97.

- Villegas S, Rosenthal J, O’Brien K, Pecora P. Health outcomes for adults in family foster care as children: An analysis by ethnicity. Child Youth Serv Rev 2011;33:110-17.

- Zlotnick C, Tam TW, Soman LA. Life course outcomes on mental and physical health: the impact of foster care on adulthood. Am J Public Health 2012;102:534-40.

- von Borczykowski A, Vinnerljung B, Hjern A. Alcohol and drug abuse among young adults who grew up in substitute care – findings from a Swedish national cohort study. Child Youth Serv Rev 2013;35:1954-61.

- Bruskas D, Tessin DH. Adverse childhood experiences and psychosocial well-being of women who were in foster care as children. Perm J 2013;17:e131-41.

- Ahrens KR, Garrison MM, Courtney ME. Health outcomes in;young adults from foster care and economically diverse backgrounds. Pediatrics 2014;134:1067-74.

- Vinnerljung B, Hjern A. Consumption of psychotropic drugs among adults who were in societal care during their childhood-A Swedish national cohort study. Nord J Psychiatry 2014;68:611-9.

- Socialstyrelsen. Tandhälsa bland unga vuxna som varit placerade. Barns och ungas hälsa, vård och omsorg 2013. Artikelnummer: 2013-3-15. ISBN: 978-91-7555-042-8.

- Socialstyrelsen. Vård och omsorg om placerade barn. Öppna jämförelser och utvärdering. Rekommendationer till kommuner och landsting om hälsa och utsatthet. Artikelnummer: 2013-3-7.

- Berlin M, Mensah T, Lundgren F, Klingberg G, Hjern A, Vinnerljung B, Cederlund A. Dental health care utilization among young adults who were in societal out-of-home care as children: A Swedish national cohort study. Int J Soc Welf (In press).

- Vinnerljung B. Mortalitet bland fosterbarn som placerats före tonåren [Mortality among foster children placed before their teens]. Socialvetenskaplig Tidskrift 1995;2:60-72.

- Barth R, Blackwell, D. Death rates among California’s foster care and former foster care populations. Child Youth Serv Rev 1998;20:577-604.

- Christoffersen MN. Risikofaktorer i barndommen [Childhood risk factors]. Copenhagen: Socialforskningsinstituttet, Rapport 99:18 1999.

- Kalland M, Pensola TH, Merilainen J, Sinkkonen J. Mortality in children registered in the Finnish child welfare registry: population based study. BMJ 2001;323:207-8.

- Vinnerljung B, Ribe M. Mortality after care among young adult foster children in Sweden. Int J Soc Welf 2001;10:164-73.

- Vinnerljung B, Berlin M, Hjern A. Skolbetyg, utbildning och risker för ogynnsam utveckling hos barn. Social Rapport 2010. Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen: 227-266, 2010.

- Björkenstam C, Björkenstam E, Ljung R, Vinnerljung B, Tuvblad C. Suicidal behavior among delinquent former child welfare clients. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2013a;22:349-55.

- Hjern A, Vinnerljung B, Lindblad F. Avoidable mortality among child welfare recipients and intercountry adoptees: a national cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2004;58:412-7.

- Gao M, Brännstrom L, Almquist YB. Exposure to out-of-home care in childhood and adult all-cause mortality: a cohort study. Int J Epidemiol 2017;46:1010-17.

- Brännström L, Vinnerljung B, Hjern A. Child welfare clients have higher risks for teenage childbirths: which are the major confounders? Eur J Public Health 2016;26:592-7.

- Brännström L, Vinnerljung B, Hjern A. Risk Factors for Teenage Childbirths among Child Welfare Clients: Findings from Sweden. Child Youth Serv Rev 2015;53:44-51.

- Vinnerljung B, Franzén E, Danielsson M. Teenage parenthood among child welfare clients: A Swedish national cohort study of prevalence and odds. J Adolesc 2007;30:97-116.

- Williams J, Jackson S, Maddocks A, Cheung W-Y, Love A, Hutchings H. Case-control study of the health of those looked after by local authorities. Arch Dis Child 2001;85:280-85.

- Ashton-Key M, Jorge E. Does providing social services with information and advice on immunisation status of “looked after children” improve uptake? Arch Dis Child 2003;88:299-301.

- Morritt J. The health needs of children in public care: the results of an audit of immunizations of children in care. Public Health 2003;117:412-6.

- Rodrigues VC. Health of children looked after by the local authorities. Public Health 2004;118:370-76.

- Barnes P, Price L, Maddocks A, Cheung WY, Williams J, Jackson S, Mason B. Immunisation status in the public care system: a comparative study. Vaccine 2005;23:2820-3.

- Hill C, Mather M, Goddard J. Cross sectional survey of meningococcal. C immunisation in children looked after by local authorities and those living at home. BMJ 2003;326:364-5.

- Walton SB, Bedford H. Immunization of looked-after children and young people: a review of the literature. Child Care Health Dev 2017;43:463-80.

- McIntyre A, Keesler T. Psychological disorders among foster children. J Clin Child Psychol 1986;15:297-303.

- McCann JB, James A, Wilson S, Dunn G. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in young people in the care system. BMJ 1996;313:1529-30.

- Stein E, Evans B, Mazumdar R, Rae-Grant N. The mental health of children in foster care: A comparison with community and clinical samples. Can J Psychiatry 1996;41:385-91.

- Dimigen G, Del Priore C, Butler S, Evans S, Ferguson L, Swan M. Psychiatric disorder among children at time of entering local authority care: questionnaire survey. BMJ 1999;319:675.

- Kjelsberg E, Nygren P. The prevalence of emotional and behavioural problems in institutionalized childcare clients. Nord J Psychiatry 2004;58:319-25.

- Minnis H, Everett K, Pelosi AJ, Dunn J, Knapp M. Children in foster care: mental health, service use and costs. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006;15:63-70.

- Ford T, Vostanis P, Meltzer H, Goodman R. Psychiatric disorder among British children looked after by local authorities: comparison with children living in private households. Br J Psychiatry 2007;190:319-25.

- Sawyer M, Carbone J, Serle A, Robinson P. The mental health and wellbeing of children and adolescents in home-based foster care. Med J Aust 2007;186:181-84.

- Schmid M, Goldbeck L, Nuetzel J, Fegert JM. Prevalence of mental disorders among adolescents in German youth welfare institutions. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2008;2:1-8.

- McAuley C, Davis T. Emotional well-being and mental health of looked after children in England. Child Fam Soc Work 2009;14:147-55.

- Egelund T, Lausten M. Prevalence of mental health problems among childrenplaced in out-of-home care in Denmark. Child Fam Soc Work 2009;14:156-65.

- Pecora P, White C, Jackson L, Wiggins T. Mental health of current and former recipients of foster care: a review of recent studies in the USA. Child Fam Soc Work 2009;14:132-46.

- Damnjanovic M, Lakic A, Stevanovic D, Johanovic A. Effects of mental health on quality of life in children and adolescents living in residential and foster care: a cross-sectional study. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2011;20:257-62.

- Lehmann S, Havik OE, Havik T, Heiervang ER. Mental disorders in foster children: a study of prevalence, comorbidity and risk factors. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2013;7:39.

- Havnen K, Breivik K, Jakobsen R. Stability and change – a 7- to 8-year follow-up study of mental health problems in Norwegian children in long-term out-of-home care. Child Fam Soc Work 2014;19:292-303.

- Maaskant A, van Rooij F, Hermanns J. Mental health and associated risk factors of Dutch school aged foster children placed in long-term foster care. Child Youth Serv Rev 2014;44:207-16.

- Sainero A, Bravo A, del Valle J. Examining needs and refferals to mental health services for children in residential care in Spain: An empirical study in an autonomous community. J Emot Behav Disord 2014;22:16-26.

- Cohn A-M, Szilagyi M, Jee S, Blumkin A, Szilagyi P. Mental health outcomes among child welfare investigated children: In-home versus out-of-home care. Child Youth Serv Rev 2015;57:106-11.

- Greger HK, Myhre AK, Lydersen S, Jozefiak T. Previous maltreatment and present mental health in a high-risk adolescent population. Child Abuse Negl 2015;45:122-34.

- Bronsard G, Alessandrini M, Fond G, Loundou A, Auquier P, Tordjman S, Boyer L. The Prevalence of Mental Disorders Among Children and Adolescents in the Child Welfare System: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e2622.

- Jozefiak T, Kayed NS, Rimehaug T, Wormdal AK, Brubakk AM, Wichstrom L. Prevalence and comorbidity of mental disorders among adolescents living in residential youth care. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2016;25:33-47.

- Gonzalez-Garcia C, Bravo A, Arruabarrena I, Martin E, Santos I, Del Valle J. Emotional and behavioral problems of children in residential care: Screening detection and referrals to mental health services. Child Youth Serv Rev 2017;73:100-06.

- Vasileva M, Petermann F. Mental health needs and therapeutic utilization of young children in foster care in Germany. Child Youth Serv Rev 2017;75:69-76.

- Zito JM, Safer DJ, Sai D, Gardner JF, Thomas D, Coombes P, Dubowski M, Mendez-Lewis M. Psychotropic medication patterns among youth in foster care. Pediatrics 2008;121:e157–e63.

- Socialstyrelsen. Förskrivning av psykofarmaka till placerade barn och ungdomar. Artikelnummer: 2014-11-3. ISBN: 978-91-7555-235-4.

- Tai M-H, Shaw T, dosReis S. Antipsychotic use and foster care placement stability among youth with attention-deficit hyperactivity/disruptive behavior disorders. J Public Child Welf 2016;10:376-90.

- Haysom L, Indig D, Byun R, Moore E, van den Dolder P. Oral health and risk factors for dental disease of Australian young people in custody. J Paediatr Child Health 2015;51:545-51.

- Melbye ML, Chi DL, Milgrom P, Huebner CE, Grembowski D. Washington state foster care: dental utilization and expenditures. J Public Health Dent 2014;74:93-101.

- Swire MR, Kavaler F. The health status of foster children. Child Welfare 1977;56:635-53.

- Olivan G. Untreated dental caries is common among 6 to 12-year-old physically abused/neglected children in Spain. Eur J Public Health 2003;13:91-2.

- Socialstyrelsen. Tandhälsa bland unga vuxna som varit placerade. Registerstudie av tandhälsa och tandvårdskonsumtion bland 20–29-åringar som varit placerade i heldygnsvård under uppväxten. Artikelnummer: 2016-2-28.

- Sveriges Kommuner och Landsting (2017). Nationell kartläggning om hälsoundersökning av barn och unga vid placering. ISBN 978-91-7585-483-0.

- Phillips J. Meeting the psychiatric needs of children in foster care: Social workers’ view. Psychiatric Bullentin 1997;21:609-11.

- Mount J, Lister A, Bennun I. Identifying the mental health needs of looked after young people. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 2004;9:363-82.

- Butterworth S, Singh S, Birchwood M, Islam Z, Munro E, Vostanis P, Paul M, Khan A, Simkiss D. Transitioning care-leavers with mental health needs: ‘They set you up to fail’. Child Adolesc Ment Health 2017;22:138-47.

- Vinnerljung B, Hjern A (2018). Health care in Europe for children in societal out-of-home care. Rapport till EU-kommissionen från MOCHA – Models of Child Health Appraised. London: MOCHA/Imperial College. http://www.childhealthservicemodels.eu/wp-content/uploads/Mocha-report-Children-in-OHC-May-2018.pdf

- Vinnerljung B, Kling S, Hjern A. Health problems and health care needs among youth in Swedish secure residential care. Int J Soc Welf (In press).

- Department of Education & Department of Health. Promoting the health and well-being of looked-after children. Statutory guidance for local authorities, clinical commissioning groups and NHS England. London: Department of Education/Department of Health 2015.

- Simkiss D, Jainer R. The English system for ensuring health care and health monitoring of looked-after children. Int J Soc Welf 2018 (In press).

- Royal College of Nursing, Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, Royal College of General Practitioners. Looked after children: Knowledge, skills and competences of health care staff. London: Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health 2015.

- Mather M, Batty D. Doctors for children in public care. London. BAAF (British Agencies for Adoption & Fostering) 2000.

- Goodman A, Goodman R. Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire scores and mental health in looked after children. Br J Psychiatry 2012;200:426-7.

- Barne-, ungdoms- og familiedirektoratet & Helsedirektoratet. Samarbeid mellom barnevernstjenster och psykiske helsetjenster till barnets bästa. Oslo: Barne-, ungdoms- og familiedirektoratet/Helsedirektoratet 2015.

- Helsedirektoratet. Barne-, ungdoms- og familiedirektoratet. Oppsummering og anbefalninger fra arbeidet med helsehjelp till barn i barnevernet. Oslo, 2017.

- Helsedirektoratet. Prioriteringsveileder – psykisk helsevern för barn og unge. Oslo, 2015.

- NOU 2016:16. Ny barnevernslov. Barne- og likestillingsdepartementet. Oslo: Norge Offentlige utredninger.

- Lehmann S. Kayed N. Mental health care for children in alternate care by the child protection services: Experiences from Norway. Int J Soc Welf (under tryckning).

- Zlotnik S, Wilson L, Scribano P, Wood JN, Noonan K. Mandates for Collaboration: Health care and child welfare policy and practice reforms create the platform for improved health for children in foster care. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 2015;45:316-22.

- Jaudes PK, Bilaver LA, Goerge RM, Masterson J, Catania C. Improving access to health care for foster children: the Illinois model. Child Welfare 2004;83:215-38.

- Simms MD. The foster care clinic: A community program to identify treatment needs of children in foster care. J Dev Behav Pediatr 1989;10:121-28.

- Jee S, Szilagyi M, Blatt S, Meguid V, Auinger P, Szilagyi P. Timely identification of mental health problems in two foster care medical homes. Child Youth Serv Rev 2010;32:685-90.

- Jaudes KP, Champagne V, Harden A, Masterson J, Bilaver LA. Expanded medical home model works for children in foster care. Child Welfare 2012;91:9-33.

- Regionförbundet Uppsala Län. Rutin och riktlinjer rörande barn och unga som utreds för samhällsvård. Uppsala: Regionförbundet Uppsala Län. 2016.

- Halldin J. Socialläkarna – mellan hälsovård och socialtjänst. Läkartidningen 2011;108:551–2.

- SBU. Utvärdering av metoder i hälso- och sjukvården. En handbok, 2 uppl. Stockholm 2014. https://www.sbu.se/metodbok.

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924-6.

- Jones R, Everson-Hock E, Guillaume L, Clapton J, Goyder E, Chilcott J, et al. The effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving access to health and mental health services for looked-after children and young people: a systematic review. Families, Relationships and Societies 2012;1:71-85.

- Richards L, Wood N, Ruiz-Calzada L. The mental health needs of loooked after children in a local authority permanent placement team and the value of the Goodman SDQ. Adoption & Fostering 2006;30:43-52.

- Janssens A, Deboutte D. Screening for psychopathology in child welfare: the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) compared with the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA). Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2009;18:691-700.

- Jee SH, Halterman JS, Szilagyi M, Conn AM, Alpert-Gillis L, Szilagyi PG. Use of a brief standardized screening instrument in a primary care setting to enhance detection of social-emotional problems among youth in foster care. Acad Pediatr 2011;11:409-13.

- Jee SH, Szilagyi M, Conn AM, Nilsen W, Toth S, Baldwin CD, Szilagyi PG. Validating office-based screening for psychosocial strengths and difficulties among youths in foster care. Pediatrics 2011;127:904-10.

- Lehmann S, Heiervang ER, Havik T, Havik OE. Screening foster children for mental disorders: properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. PLoS One 2014;9:e102134.

- Ronsalbalm K SE, Lawrence N, Coleman K, Frey J, van der Ende J, Dodge K. Child wellbeing assessment in child welfare. A review of four measures. Child Youth Serv Rev 2016;68:1-16.

- Jee SH, Szilagyi M, Ovenshire C, Norton A, Conn AM, Blumkin A, Szilagyi PG. Improved detection of developmental delays among young children in foster care. Pediatrics 2010;125:282-9.

- Jee SH, Conn AM, Szilagyi PG, Blumkin A, Baldwin CD, Szilagyi MA. Identification of social-emotional problems among young children in foster care. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2010;51:1351-8.

- Jee SH, Halterman JS, Szilagyi M, Conn AM, Alpert-Gillis L, Szilagyi PG. Use of a brief standardized screening instrument in a primary care setting to enhance detection of social-emotional problems among youth in foster care. Acad Pediatr 2011;11:409-13.

- Gallagher CA, Dobrin A. Can juvenile justice detention facilities meet the call of the American Academy of Pediatrics and National Commission on Correctional Health Care? A national analysis of current practices. Pediatrics 2007;119:e991-1001.

- Undheim AM, Lydersen S, Kayed NS. Do school teachers and primary contacts in residential youth care institutions recognize mental health problems in adolescents? Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2016;10:19.

- Bellonci C, Huefner JC, Griffith AK, Vogel-Rosen G, Smith GL, Preston S. Cocurrent reductions in psychotropic medication, assault, and physical restraint in two residential treatment programs for youths. Child Youth Serv Rev 2013;35:1773-9.

- Huefner JC, Griffith AK, Smith GL, Vollmer DG, Leslie LK. Reducing psychotropic medications in an intensive residential treatment center. J Child Fam Stud 2014;23:675-85.

- Lee TG, Walker SC, Bishop AS. The impact of psychiatric practice guidelines on medication costs and youth aggression in a juvenile justice residential treatment program. Psychiatr Serv 2016;67:214-20.

- Poynor M, Welbury J. The dental health of looked after children. Adoption & Fostering 2004;28:86-8.

- Hunter D, McCartney G, Fleming S, Guy F. Improving the health of looked after children in Scotland. Using a specialist nursing service to improve the health care of children in residential accommodation. Adoption & Fostering 2008;32:51-6.

- Williams A, Mackintosh J, Bateman B, Holland S, Rushworth A, Brooks A, Geddes J. The development of a designated dental pathway for looked after children. Br Dent J 2014;216:E6.

- Hill C, Wright V, Sampeys C, et al. The emerging role of the specialist nurse: promoting the health of looked after children. Adoption & Fostering 2002;26:35-43.

- Jaudes PK, Bilaver LA, Goerge RM, Masterson J, Catania C. Improving access to health care for foster children: the Illinois model. Child Welfare 2004;83:215-38.

- Horwitz SM, Owens P, Simms MD. Specialized assessments for children in foster care. Pediatrics 2000;106:59-66.

- Williams ME, Park S, Anaya A, Perugini SM, Rao S, Neece C, Rafeedie J. Linking infants and toddlers in foster care to early childhood mental health services. Child Youth Serv Rev 2012;34:838-44.

- Risley-Curtiss C, Stites B. Improving healthcare for children entering foster care. Child Welfare 2007;86:123-44.

- Green M, Mattsson T. Health, Rights and the State, Scandinavian Studies in Law. 2017;62:177-97.

- Barnombudsmannen. Våga fråga – röster från barn i familjehem 2014.

- Care Quality Commission (CQC). Not seen, not heard: a review of the arrangements for child safeguarding and health care for looked after children in England. Newcastle upon Thyne: Care Quality Commission 2016.

- Kling S, Nilsson I. Familjehemsplacerade skolbarns hälsa och hälsovård - uppföljning av 105 barn, 2015. Tillgänglig 2018-02-25 på http://www.allmannabarnhuset.se/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Familjehemsplacerade-skolbarns-h%C3%A4lsa-och-h%C3%A4lsov%C3%A5rd.pdf

- Vinnerljung B, Forsman H, Jacobsen H, Kling S, Kornør H, Lehman S. Barn kan inte vänta. Översikt av kunskapsläget och exempel på genomförbara förbättringar. Stockholm: Nordens Välfärdscenter, Projekt: Nordens barn – fokus på barn i fosterhem, 2015.

- SBU. Behandlingsfamiljer för ungdomar med beteendeproblem – Treatment Foster Care Oregon. En systematisk översikt och utvärdering inklusive ekonomiska och etiska aspekter. Stockholm: Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering (SBU); 2018. SBU-rapport nr 279. ISBN 978-91-88437-21-1.

- Socialstyrelsen. Individ- och familjeomsorg – Lägesrapport 2017. Artikelnummer 2017-2-14. ISBN: 978-91-7555-413-6. http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/Lists/Artikelkatalog/Attachments/20491/2017-2-14.pdf

- Department of Health. Promoting the health of looked after children. Tillgänglig 2018-03-06 på http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4060424.pdf 2002

- Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001349.

- Fryers T, Brugha T. Childhood determinants of adult psychiatric disorder. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health 2013;9:1-50.

- Dean K, Stevens H, Mortensen PB, Murray RM, Walsh E, Pedersen CB. Full spectrum of psychiatric outcomes among offspring with parental history of mental disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010;67:822-9.

- Simkiss DE, Stallard N, Thorogood M. A systematic literature review of the risk factors associated with children entering public care. Child Care Health Dev 2013;39:628-42.

- Blair C, Raver CC, Granger D, Mills-Koonce R, Hibel L, Family Life Project Key Investigators. Allostasis and allostatic load in the context of poverty in early childhood. Dev Psychopathol 2011;23:845-57.

- Gard AM, Waller R, Shaw DS, Forbes EE, Hariri AR, Hyde LW. The long reach of early adversity: Parenting, stress, and neural pathways to antisocial behavior in adulthood. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging 2017;2:582-90.

- Turney KW, Wildeman C. Adverse childhood experiences among children placed in and adopted from foster care: Evidence from a nationally representative study. Child Abuse Negl 2017;64:117-29.

- Ferraro KF, Schafer MH, Wilkinson LR. Childhood disadvantage and health problems in middle and later life: Early imprints on physical health? Am Sociol Rev 2016;81:107-33.

- Kvist T, Annerbäck E-M, Dahlöf G. Oral health in children investigated by Social services on suspicion of child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse Negl 2018;76:515-23.

- Farrington D. Crime and physical health: illnesses, injuries and accidents in the Cambridge Study. Crim Behav Ment Health1995;54:261-78.

- Wade TP, Pevalin D. Adolescent delinquency and health. Can J Criminol 2005;47:619-54.

- Felitti VJ. The relation between adverse childhood experiences and adult health: Turning gold into lead. Perm J 2002;6:44-7.

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med 1998;14:245-58.

- Chapman DP, Whitfield CL, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Edwards VJ, Anda RF. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. J Affect Disord 2004;82:217-25.

- Harkonmäki K, Korkeila K, Vathera J, Kivimäki M, Souminen S, Sillanmäki L, Koskenvuo M. Childhood adversities as a predictor of disability retirement. J Epidemiol Community Health 2007;61:479-84.

- Björkenstam E, Hjern A, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Vinnerljung B, Hallqvist J, Ljung R. Multi-exposure and clustering of adverse childhood experiences, socioeconomic differences and psychotropic medication in young adults. PLoS One 2013;8:e53551.

- Björkenstam E, Burström B, Vinnerljung B, Kosidou K. Childhood adversity and psychiatric disorder in young adulthood: An analysis of 107,704 Swedes. J Psychiatr Res 2016;77:67-75.

- Björkenstam E, Dalman C, Vinnerljung B, Weitoft GR, Walder DJ, Burström B. Childhood household dysfunction, school performance and psychiatric care utilisation in young adults: a register study of 96 399 individuals in Stockholm. J Epidemiol Community Health 2016;70:473-80.

- Björkenstam E, Hjern A, Vinnerljung B. Adverse childhood experiences and disability pension in early midlife: results from a Swedish National Cohort Study. Eur J Public Health. 2017;27:472-7.

- Björkenstam E, Vinnerljung B, Hjern A. Impact of childhood adversities on depression in early adulthood: A longitudinal cohort study of 478,141 individuals in Sweden. J Affect Disord 2017;223:95-100

- Basto-Pereira M, Miranda A, Ribero S, Maia A. Growing up with adversity: From juvenile justice involvement to criminal persistence and psychosocial problems in young adulthood. Child Abuse Negl 2016;62:63-75.

- Fridell Lif E, Bränsström L, Vinnerljung B, Hjern A. Childhood adversities and later economic hardship among child welfare clients: Cumulative disadvantage or disadvantage saturation? Br J Soc Work 2017;47:2137-56.

- Rebbe R, Nurius PS, Aharens KR, Courtney ME. Adverse childhood experiences among youth aging out of foster care: A latent class analysis. Child Youth Serv Rev 2017;74:108-16.

- Butler I, Payne H. The health of children looked after by the local authority. Adoption & Fostering 1997;21:28-35.

- Ward H, Jones H, Lynch M, Skuse T. Issues concerning the health of looked after children. Adoption & Fostering 2002;26:8-18.

- Kling S. Fosterbarns hälsa - det medicinska omhändertagandet av samhällsvårdande barns hälsa i Malmö. Malmö stad 2010.

- Hultman E, Cederborg A-C, Alm C, Fählt Magnusson K. Vulnerable children’s health as described in investigations of reported children. Child Fam Soc Work 2013;18:117-28.

- Blennow M, Fiedler Backteman U, Lindfors A. Hälsovård för barn placerade I samhällsvård. Brister finns, förbättringar möjliga. Stockholm: Stockholms läns landsting 2014.

- Swank JM, Gagnon JC. A national survey of mental health screening and assessment practices in juvenile correctional facilities. Child Youth Care Forum 2017;46:379-93.

- Hochstadt NJ, Jaudes PK, Zimo DA, Schachter J. The medical and psychosocial needs of children entering foster care. Child Abuse Negl 1987;11:53-62.

- Child Welfare League of America (CWLA). Standards for health care services for children in out-of-home care. Washington, DC: CWLA, 1988.

- American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). Health care of children in foster care. Pediatrics 1994;93:335-8.

- American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). Health care for children and youth in the juvenile correctional care system. Pediatrics 2001;107:799–803.

- American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). Health care of young children in foster care. Pediatrics 2002;109:536-41.

- American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). Health care for youth in the juvenile justice system. Policy statement. Pediatrics 2011;128:1219–35.

- Leslie LK, Hurlburt MS, Landsverk J, Rolls JA, Wood PA, Kelleher KJ. Comprehensive assessments for children entering foster care: a national perspective. Pediatrics 2003;112:134-42.

- Leve LD, Harold GT, Chamberlain P, Landsverk JA, Fisher PA, Vostanis P. Practitioner review: Children in foster care-vulnerabilities and evidence-based interventions that promote resilience processes. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2012;53:1197-211.

- Luke N, Sinclair I, Woolgar M, Sebba J. What works in preventing and treating poor mental health in looked after children? London: NSPCC & Oxford: The Rees Centre, University of Oxford 2014.

- SBU. Tandförluster. En systematisk litteraturöversikt. Stockholm: Statens beredning för medicinsk utvärdering (SBU); 2010. SBU-rapport nr 204. ISBN 978-91-85413-40-9.

- Alsfjell J, Stenberg J. Psykiatriska diagnoser och förändringar hos en grupp SiS-ungdomar. Allmän SiS-rapport, 2008:4. Stockholm: Statens institutionsstyrelse.

- Ståhlberg O, Anckarsäter H, Nilsson T. Mental Health Problems in youth committed to juvenile institutions: prevalences and treatment needs. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2010;19:893-903.

- Kling S, Nilsson I. Fysisk och psykisk hälsa hos barn som utreds inom socialtjänsten. Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen 2015.

Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services

Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook

Share on LinkedIn

Share on LinkedIn

Share via Email

Share via Email