Effects of active labour market programs for long-term social assistance recipients

A systematic review

Conclusions

- Training received at workplaces is more effective than interventions as usual or no intervention for long-term social assistance recipients to take and hold an employment (moderate certainty of evidence).

- Extensive or long-term training is more effective than interventions as usual or no intervention for long-term social assistance recipients to take and hold an employment (moderate certainty of evidence).

- Work supporting program in regular/ordinary municipal activities is more effective than work supporting programs outside regular work activities for long-term social assistance recipients to take and hold an employment (moderate certainty of evidence). Working in business that are government controlled during recession can be non-existent or negligible for young people compared to no intervention (low certainty).

- Reduced case manager workload i.e., less clients and a possibility of intensified management for each client, supports long-term social assistance recipients to take and hold an employment compared to working as usual (low certainty of evidence).

- The effect on entry or return to work for long-term social assistance recipients can be non-existent or negligible regarding the following interventions:

- classroom training (low certainty of evidence)

- work program with bonus (low certainty of evidence)

- employer subsidies (low certainty of evidence)

- extensive case manager assessment and follow up (low certainty of evidence).

- The effect on entry or return to work for long-term social assistance recipients could not be assessed regarding following interventions:

- various supportive preparatory programs including start-up-capital intervention (very low certainty of evidence)

- job search assistance (very low certainty of evidence).

Background

Persons in working age that do not regularly take part on the labour market may need support from the society through labour market interventions. One such group is individuals with lasting social assistance, i.e., long-term social assistance recipients.

For most adults, holding a job means taking part in meaningful tasks and having a better financial situation. Work can also affect health or vice versa.

Aim

The purpose of this project was to investigate the body of evidence regarding labour market interventions for persons outside the labour market. A broad definition of this was adults, aged 18-64 years, on long-term sick leave or long-term social assistance, respectively. This review presents the results regarding long-term social assistance recipients. Another review presents the results regarding persons on long-term sick leave due to mild or moderate depression, anxiety, or reactions to severe stress.

Method

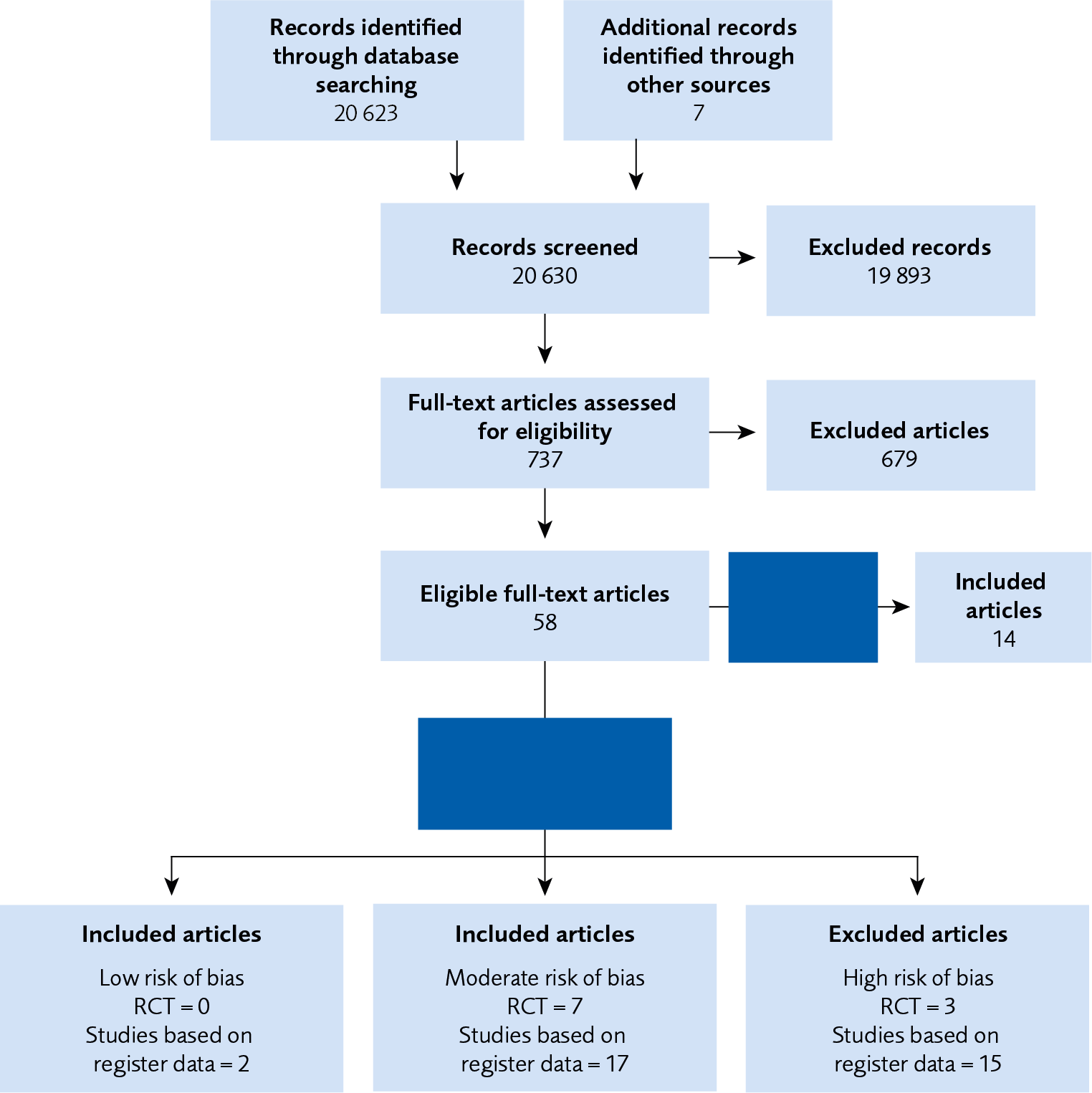

This systematic review is conducted in accordance with the PRISMA statement and SBU’s methodology (www.sbu.se/en/method). The protocol is registered in Prospero, CRD42021235586. Quantitative and qualitative studies with low or moderate risk of bias published during the period 2000 to 2021 were included. Dialogues were held with reference groups representing client or patient perspectives, as well as perspectives from some different Swedish authorities of relevance. The certainty of evidence was assessed according to the GRADE-system.

Inclusion criteria:

Population

Adult persons, aged 18-64 years being outside of the labour market, receiving social assistance during at least six months, alone or combined with other financial replacements. They should be assessed as having the ability to work.

Intervention

Labour market interventions that are, or could be, used in Sweden. Four types of interventions, lasting for at least one month, were defined as:

- preparatory programs, e.g., job search assistance or counselling

- training

- workplace practice

- other interventions such as work-related rehabilitation, self-employment etc.

Control

No intervention, intervention as usual, or other measures.

Outcome

Primary: employment in the labour market, started or finalized education, income.

Secondary: health measures such as sleep, depression, anxiety, stress, quality of life or capacity for work.

Study design

Randomized controlled studies, RCT, quasi-experimental observation studies based on register data as well as studies based on qualitative data.

Language: English, Swedish, Norwegian, Danish.

Search period: 1995 to 2022. Final search was conducted on February 2, 2022.

Databases searched:

- Scopus (Elsevier)

- Ebsco Multi-Search (SocINDEX with Full Text; Academic Search Premier; ERIC)

- Sociological Abstracts (ProQuest)

- EconLit (Ebsco).

Client involvement: No.

Results

The effects of one or more active labour market interventions are based on 26 quantitative studies, seven randomized controlled studies and 19 studies based on register data. The studies were from ten countries, seven from Germany, four from USA and Denmark, respectively, three from the Netherlands, two from Norway and Argentina, respectively, and one from Australia, UK, Spain and Sweden, respectively. In total, about 5.8 million persons participated in the studies. 14 studies with qualitative data were also included in the review, out of which five were relevant to a Swedish context.

| Outcome | Effect | GRADE – assessed certainty of evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Intervention= preparatory program |

Various preparatory program interventions result in more persons to take and hold an employment for follow up at ≤ 20 months compared to job search support. | Low certainty of evidence |

| EmploymentIntervention= support + training |

The effect of preparatory program in the form of individual support and work-training could not be assessed on employment. | Very low certainty of evidence |

| EmploymentIntervention= support + start your own business-capital |

The effect of preparatory program in the form of work-support and capital to start your own business on employment could not be assessed. | Very low certainty of evidence |

| IncomeIntervention= temporary job |

Preparatory program in the form of temporary job interventions results in higher income for the participant for follow up at ≤ two years compared to direct hire. | Low certainty of evidence |

| IncomeIntervention= support + training |

The effect of preparatory programs in the form of individual support and training on income could not be assessed. | Very low certainty of evidence |

| IncomeIntervention= support + start-up-capital |

The effect of preparatory programs in the form of support and capital to start your own business on income could not be assessed. | Very low certainty of evidence |

| Outcome | Effect | GRADE |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Intervention= classroom training |

The effect on employment from classroom training can be non-existent or negligible compared to a usual or no intervention. | Low certainty of evidence |

| Employment Intervention= workplace training |

Workplace training results in more persons holding an employment after 12-28 months compared to a usual or no intervention. | Moderate certainty of evidence |

| Employment Intervention= extensive training |

Workplace training results in more persons holding an employment after 12-28 months, compared to a usual or no intervention. | Moderate certainty of evidence |

| Income All forms of training |

All forms of training leads to increased income after 12 months compared to usual intervention. The effect was more pronounced for males. | Low certainty of evidence |

| Outcome | Effect | GRADE |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Intervention= workplace practice + a direct financial incentive for the person |

The effect on employment from workplace practice combined with a direct financial incentive for the person can be non-existent or negligible compared to a usual or no intervention. | Low certainty of evidence |

| Employment Intervention= workplace practice without a direct financial incentive for the person |

Workplace practice without a direct financial incentive for the person results in more adults and young people holding an employment for follow up at ≤ three years. | Moderate certainty of evidence |

| Employment Intervention= workplace practice without a direct financial incentive for the person |

Workplace practice in the public sector without a direct financial incentive for the person results in more immigrants receiving and holding an employment for follow up at ≤ five years. | Low certainty of evidence |

| Employment Intervention= workplace practice without a direct financial incentive for the person (recession) |

The effect on employment or education from workplace practice (without a direct financial incentive for the person) can be non-existent or negligible, for young persons during a recession, for follow up at ≤ three years compared to no intervention. | Low certainty of evidence |

| Income Intervention= workplace practice + a direct financial incentive for the person |

The effect on income from workplace practice combined with a direct financial incentive for the person can be non-existent or negligible for follow up at ≤ five years compared to a usual or no intervention. | Low certainty of evidence |

| Income Intervention= workplace practice without a direct financial incentive for the person |

Workplace practice without a direct financial incentive for the person results in higher income for both adults and young persons for follow up at ≤ three years compared to a usual intervention. | Low certainty of evidence |

| Outcome | Effect | GRADE |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Intervention= employer subsidies |

The effect of employer subsidies compared to a usual or no intervention on employment can be non-existent or negligible at follow up ≤ 12 months compared to a usual or no intervention. | Low certainty of evidence |

| Income Intervention= employer subsidies |

The effect on income from employer subsidies could not be assessed. | Very low certainty of evidence |

| Outcome | Effect | GRADE |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Intervention= less clients per case manager |

Fewer clients per case manager results in persons having the ability to work longer hours at 12 months follow up compared to case manager routine work. | Low certainty of evidence |

| Employment Intervention= comprehensive assessment and client follow up |

The effect on employment can be non-existent or negligible from comprehensive assessment and client follow-up at ≤ 30 months compared to case manager routine work or no intervention. | Low certainty of evidence |

| Income Intervention= comprehensive assessment and client follow up |

The effect on income can be non-existent or negligible from comprehensive assessment and client follow-up after six months compared to other case manager intervention. | Low certainty of evidence |

Health Economic Assessment

Two financial evaluations of the studied labour market interventions were included. Both studies evaluated interventions in the category workplace practice combined with financial bonus for the individual. Both evaluations were simpler financial analyses focusing on whether the income increase for the participants exceeds the intervention costs.

Ethics

The main purpose of a labour market intervention is to increase the possibility that an individual, who are outside of the labour market, receives an employment. From an ethical perspective, however, this purpose is an instrumental goal whose fulfilment is only of value if it in turn leads to other states that have final value. There are two different perspectives on what could constitute this final value. One perspective is strictly socioeconomical and the other is an individual perspective based on the needs of the individual.

Discussion

The studies were performed in the Nordic countries, other European countries, North and South America and Australia. These countries have different labour market policy and welfare subsidies. Thus, the study results from the different studies should be interpreted with some caution, particularly results from studies in countries with welfare systems which obviously differ from the ones in Swedish and other Nordic countries.

The results in this review indicate that immigrants may benefit more from training and workplace practice than non-immigrants. Further, there is very little information in the included studies concerning participant employment quality.

For a number of active labour market interventions, effects on entry or return to work could not be assessed. It depends, among other things, on that the interventions differ from one another and thereby their results cannot be added together. Other reasons are the various measurement of effect and insufficient study data that cannot be used for statistical syntheses. When the data about effects on employment from the interventions are insufficient, the authors have not assessed the certainty of evidence. A very low certainty of evidence should, however, does not necessarily mean that there is no effect. Instead, it emphasizes the need for further intervention evaluation in well performed studies.

It would be valuable with a consensus regarding what is most important to measure and how it may be measured in an agreed list of prioritized results, a Core Outcome Set (COS). According to the organization COMET (Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials), there is ongoing work to bring forth a COS for “work participation”, but at present nothing is yet published.

From studies based on qualitative data, there appears to be a discrepancy between official ambitions and descriptions of intervention designs and effects on the one hand, and participant experiences and skepticism on the other hand.

Conflicts of Interest

In accordance with SBU’s requirements, the experts and scientific reviewers participating in this project have submitted statements about conflicts of interest. These documents are available at SBU’s secretariat. SBU has determined that the conditions described in the submissions are compatible with SBU’s requirements for objectivity and impartiality.

Link to the Swedish report:

Effekter av arbetsmarknadsinsatser för personer med varaktigt försörjningsstöd

Project group

Experts

- Tapio Salonen, professor, social work, Malmö university, Sweden

- Per Johansson, professor, statistics, Uppsala university, Sweden

- Elisabeth Furberg, associate professor, philosophy, Stockholm university, Sweden

- Peter Thoursie, professor, political economy, Stockholm university, Sweden

- Elisabeth Björk Brämberg, associate professor, occupational medicine, Karolinska institutet, Sweden

SBU

- Elizabeth Åhsberg, project manager, PhD

- Gunilla Fahlström, assistant project manager, Dr Med Sci.

External reviewers

- Edward Palmer, Stockholm, Sweden

- Ilse Julkonen, University of Helsingfors, Finland

Flow chart of included studies

Appendices

References

- SBU. Effekter av arbetsmarknadsinsatser för personer långvarigt sjukskrivna på grund av depression, ångest eller stressreaktion. Stockholm: Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering (SBU); 2022. SBU Utvärderar 352. [accessed date]. Available from: https://www.sbu.se/352.

- Janlert U. Arbete, arbetslöshet och jämlik hälsa – en kunskapsöversikt; 2016 S2015:02.

- Norström F, Waernerlund A, Lindholm L, Nygren R, Sahlén K, Brydsten A. Does unemployment contribute to poorer health-related quality of life among Swedish adults? BMC Public Health. 2019(19):457.

- Paul K, Moser K. Unemployment impairs mental health: Meta-analyses. J Vocat Behav. 2009(74):264-82.

- Mörk E, Ottosson L, Vikman U. To work or not to work? Effects of temporary public employment on future employment and benefits. Working paper 2021:16 Institute for evaluation of labour market and education policy, Uppsala.

- Caliendo M, Mahlstedt R, van de Berg, G, Vikström J. Hälsoeffekter av arbetsmarknadspolitiska insatser. Uppsala: IFAU; 2020.

- Baigi A, Lindgren E-C, Starrin B, Bergh H. In the shadow of the welfare society ill-health and symptoms, psychological exposure and lifestyle habits among social security recipients: A national survey study. BioPsychoSocial Medicine. 2008;2. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/1751-0759-2-15.

- Løyland B, Miaskowski C, Dahl E, Paul SM, Rustøen T. Psychological distress and quality of life in long-term social assistance recipients compared to the Norwegian population. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(3):303-11. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494811401475.

- Løyland B, Miaskowski C, Wahl AK, Rustøen T. Prevalence and characteristics of chronic pain among long-term social assistance recipients compared to the general population in Norway. Clinical Journal of Pain. 2010;26(7):624-30. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181e0de43.

- SBU. Utvärdering av metoder i hälso- och sjukvården och insatser i socialtjänsten: en metodbok. Stockholm: Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering (SBU); 2020. [accessed Sep 20 2021]. Available from: https://www.sbu.se/metodbok.

- van der Noordt M, Ijzelenberg H, Droomers M, Proper K. Health effects of employment: a systematic review of prospective studies Occupational Environmental Health. 2014(71):730-6. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2013-101891.

- Vingård E. Psykisk ohälsa, arbetsliv och sjukfrånvaro. Uppdaterad version. Forte; 2020.

- Socialstyrelsen. Försörjningshinder och ändamål med ekonomiskt bistånd 2020. Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen; 2020. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/statistik/2021-10-7600.pdf.

- Socialstyrelsen. Ekonomiskt bistånd, Handbok för socialtjänsten.Stockholm.: Socialstyrelsen 2021 2021-5-7389. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/handbocker/2021-5-7389.pdf.

- Socialstyrelsen. Statistik om ekonomiskt bistånd 2020. Stockholm; 2021 2021-6-7466. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/statistik/2021-6-7466.pdf.

- Socialstyrelsen. Ekonomiskt bistånd/Socialbidrag 2000. Stockholm; 2001 Socialtjänst 2001:7.

- Socialstyrelsen. Försörjningshinder och ändamål med ekonomiskt bistånd 2020. Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen; 2021 2021-10-7600. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/statistik/2021-10-7600.pdf.

- Vikman U, Westerberg A. Arbetar kommunerna på samma sätt? Om kommunal variation inom arbetsmarknadspolitiken: IFAU; 2017. Available from: https://www.ifau.se/Forskning/Publikationer/Rapporter/2017/arbetar-kommunerna-pa-samma-satt-om-kommunal-variation-inom-arbetsmarknadspolitiken/.

- Forslund A. Kommunal arbetsmarknadspolitik. Vad och för vem? En beskrivning utifrån ett unikt datamaterial. Uppsala: IFAU; 2019. Available from: https://www.ifau.se/globalassets/pdf/se/2019/r-2019-05-kommunal-arbetsmarknadspolitik-vad-och-for-vem.pdf.

- Socialstyrelsen. Jobbstimulans inom ekonomiskt bistånd. En uppföljning: Socialstyrelsen; 2016.

- Panican A. Jonsson H. Strategies Against Poverty in a Social Democratic Local Welfare System: Still the Responsibility of Public Actors? In: Combating Poverty in Local Welfare Systems Work and Welfare in Europe. London: Palgrave Macmillan; 2016.

- Thorén K. Arbetsmarknadspolitik i kommunerna. Stockholm: Riksdagen; 2012. Available from: https://data.riksdagen.se/fil/3DA8340C-05F3-441A-93ED-F4778441CA14.

- Nybom J. Aktivering av socialbidragstagare – om stöd och kontroll i socialtjänsten. Stockholm: Institutionen för socialt arbete - Socialhögskolan, Stockholms universitet; 2012.

- Ulmestig R. På gränsen till fattigvård? : En studie om arbetsmarknadspolitik och socialbidrag. Lund: Lunds universitet Socialhögskolan; 2007. Available from: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:227875/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

- SKR. Kommunal arbetsmarknadsstatistik 2020. Kolada – statistik och databank. Stockholm: SKR- Sveriges Kommuner och Regioner; 2020. Available from: https://skr.se/download/18.5627773817e39e979ef5d0fe/1642497608710/7585-941-5.pdf.

- Lundin E. Motståndets betydelse – Ett bidrag till aktör-strukturdebatten. Sociologisk forskning. 2008;45(4):46-72. Available from: https://doi.org/http://du.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:866614/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

- Ulmestig R. Individualisering och arbetslösa ungdomar. Arbetsmarknad och Arbetsliv. 2010(3). Available from: https://doi.org/http://kau.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:712683/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

- Ulmestig. En studie i och om variationer: En kartläggning av socialbidragshandläggning i Jönköpings län. Växjö: Växjö universitet, Fakulteten för humaniora och samhällsvetenskap, Institutionen för vårdvetenskap och socialt arbete.; 2009.

- Panican A. Ulmestig R. Vad är nytt? – Kunskapssammanställning av kommunal arbetsmarknadspolitik. Arbetsmarknad och Arbetsliv. 2019;25(3-4).

- Ulmestig R. Gränser och variationer – en studie om insatser inom kommunal arbetsmarknadspolitik. Uppsala: IFAU – Instituet för arbetsmarknads-och utbildningspolitisk utvärdering; 2020. Available from: https://www.ifau.se/globalassets/pdf/se/2020/r-2020-5-granser-och-variationer--en-studie-om-insatser-inom-kommunal-arbetsmarknadspolitik.pdf.

- Forslund A, Skans Nordström Oskar. Swedish youth labour market policies revisited: IFAU; 2006.

- Giertz A. Making the Poor work - Social assistance and Activations Programs in Sweden. Lund 2004. Available from: https://lup.lub.lu.se/search/files/4715275/1693304.pdf.

- Hallsten L BK, Gustafsson K. Utbränning i Sverige – en populationsstudie. Stockholm: Arbetslivsinstitutet; 2002.

- Milton P. Arbete i stället för bidrag? Om aktiveringskraven i socialtjänsten och effekten för de arbetslösa bidragstagarna. Uppsala: Uppsala universitet; 2006.

- Dahlberg, M, Hanspers, K, Mörk, E. Mandatory activation of welfare recipients – evidence from the city of Stockholm, in Hanspers, Essays on welfare dependency and privatization of welfare services. Uppsala universitet: Nationalekonomiska institutionen; 2013.

- Persson A, Vikman, U. The effects of mandatory activiation on welfare entry and exit rates. Safety Nets and Benefit Dependence Research in Labor Economics. 2014;39:189-217.

- Nybom M, Stuhler J. Interpreting trends intergenerational mobility. Stockkholm: Stockholms universitet; 2014. Available from: http://su.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:703986/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

- Rayyan; 2016. Rayyan – a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews.

- Sterne JAC, Savovic J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ Open. 2019;366:l4898. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4898.

- Schünemann HJ, Carlos Cuello C, Akl EA, Mustafa R, Meerpoh JJ, Thayer K, et al. GRADE Guidelines: 18. How ROBINS-I and other tools to assess risk of bias in non-randomized studies should be used to rate the certainty of a body of evidence. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2019;111:105-14. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.01.012.

- CMT. Tröskelvärden och kostnadseffektivitet – innebörd och implikationer för ekonomiska utvärderingar och beslutsfattande i hälso- och sjukvården. Linköpings universitet: Centrum för utvärdering av medicinsk teknologi; 2018. Available from: https://liu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1267099/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

- Hultkrantz, Vimefall. Samhällsekonomisk nyttokostnadsanalys: Lund: Studentlitteratur AB; 2020.

- Persson. Hälsoekonomi – begrepp och tillämpningar. 2019.

- SBU. Etiska aspekter på insatser inom det sociala området. En vägledning för att identifiera relevanta etiska frågor. Stockholm: Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering (SBU); 2019. Available from: https://www.sbu.se/globalassets/ebm/etiska_aspekter_sociala_omradet.pdf

- SBU. Etiska aspekter på insatser inom hälso- och sjukvården. En vägledning för att identifiera relevanta etiska aspekter. Stockholm: Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering (SBU); 2021. Available from: https://www.sbu.se/globalassets/ebm/etiska_aspekter_halso_sjukvarden.pdf.

- Markussen S, Røed K. Leaving poverty behind? The effects of generous income support paired with activation. Am Econ J Econ Policy. 2016;8(1):180-211.

- Ayala L, Rodríguez M. Evaluating social assistance reforms under programme heterogeneity and alternative measures of success. Int J Soc Welf. 2013;22(4):406-19.

- Autor D, Houseman S. Temporary Agency Employment as a Way out of Poverty? 2005.

- Harrer T, Moczall A, Wolff J. Free, free, set them free? Are programmes effective that allow job centres considerable freedom to choose the exact design? Int J Soc Welf. 2020;29(2):154-67.

- Meckstroth A, Moore Q, Burwick A, Heflin C, Ponza M, McCay J. Experimental evidence of a work support strategy that is effective for at-risk families: The building Nebraska families program. Social Service Review. 2019;93(3):389-428.

- Bernhard S, Kopf E. Courses or individual counselling: does job search assistance work? Appl Econ. 2014;46(27):3261-73.

- Almeida RK, Galasso E. Jump-starting self-employment? Evidence for welfare participants in Argentina. World Dev. 2010;38(5):742-55.

- Dengler K. Effectiveness of Active Labour Market Programmes on the Job Quality of Welfare Recipients in Germany. J Soc Policy. 2019;48(4):807-38.

- Kopf E. Short training for welfare recipients in Germany: Which types work? Int J Manpow. 2013;34(5):486-516.

- Heinesen E, Husted L, Rosholm M. The effects of active labour market policies for immigrants receiving social assistance in Denmark. IZA J Migr. 2013;2(1).

- Brenninkmeijer V, Blonk RWB. The effectiveness of the JOBS program among the long-term unemployed: A randomized experiment in the Netherlands. Health Promot Int. 2012;27(2):220-9.

- Harrer T, Stockinger B. First step and last resort: One-Euro-Jobs after the reform. J Soc Policy. 2021.

- Hohmeyer K, Wolff J. A fistful of euros: Is the German one-euro job workfare scheme effective for participants? Int J Soc Welf. 2012;21(2):174-85.

- Huber M, Lechner M, Wunsch C, Walter T. Do German Welfare-to-Work Programmes Reduce Welfare Dependency and Increase Employment? Ger Econ Rev. 2011;12(2):182-204.

- Knoef M, Ours JC. How to stimulate single mothers on welfare to find a job: evidence from a policy experiment. J Popul Econ. 2016;29(4):1025-61.

- Arendt JN, Kolodziejczyk C. The Effects of an Employment Bonus for Long-Term Social Assistance Recipients. Journal of Labor Research. 2019;40(4):412-27.

- Dorsett R, Robins PK. A Multilevel Analysis of the Impacts of Services Provided by the U.K. Employment Retention and Advancement Demonstration. Evaluation Review. 2013;37(2):63-108.

- Bloom D. Jobs First: Final Report on Connecticut's Welfare Reform Initiative; 2002.

- Cammeraat E, Jongen E, Koning P. Preventing NEETs during the Great Recession: the effects of mandatory activation programs for young welfare recipients. Empir Econ. 2021.

- Graversen BK, Jensen P. A Reappraisal of the Virtues of Private Sector Employment Programmes. Scand J Econ. 2010;112(3):546-69.

- Hamersma S. The effects of an employer subsidy on employment outcomes: A study of the work opportunity and welfare-to-work tax credits. IRP Disc. 2005.

- Galasso E, Ravallion M, Salvia A. Assisting the transition from workfare to work: A randomized experiment. Ind Labor Relat Rev. 2004;58(1):128-42.

- Breunig R. Assisting the Long-Term Unemployed: Results from a Randomised Trial. Economic Record. 2003;79(244):84-102.

- Malmberg-Heimonen I, Tøge AG. Effects of individualised follow-up on activation programme participants' self-sufficiency: A cluster-randomised study. Int J Soc Welf. 2016;25(1):27-35.

- Ravn R, Nielsen K. Employment effects of investments in public employment services for disadvantaged social assistance recipients. Eur J Soc Security. 2019;21(1):42-62.

- Lundin. Arbetsmarknadspolitik för arbetslösa mottagare av försörjningsstöd: IFAU - Institutet för arbetsmarknads- och utbildningspolitisk utvärdering; 2018. Available from: https://www.ifau.se/globalassets/pdf/se/2018/r-2018-12-arbetsmarknadspolitik-for-arbetslosa-forsorjningsstodsmottagare.pdf .

- Angelin. Den dubbla vanmaktens logik: En studie om långvarig arbetslöshet och socialbidragstagande bland unga vuxna. Lund: School of social work. Lund university; 2009. Available from: https://lucris.lub.lu.se/ws/portalfiles/portal/3374520/1504325.pdf.

- Hedblom. Aktiveringspolitikens Janusansikte: En studie av differentiering, inklusion och marginalisering. Lund: School of social work. Lund university; 2004. Available from: https://lup.lub.lu.se/search/files/4715713/1693288.pdf.

- Ohls C. A qualitative study exploring matters of ill-being and well-being in Norwegian activation policy. Soc Policy Soc. 2017;16(4):593-606.

- Ohls C. Dignity-based practices in Norwegian activation work. Int J Soc Welf. 2020;29(2):168-78.

- Hansen LS, Nielsen MH. Working Less, Not More in a Workfare Programme: Group Solidarity, Informal Norms and Alternative Value Systems Amongst Activated Participants. J Soc Policy. 2021:1-17.

- Baker M, Tippin D. ‘When flexibility meets rigidity’: sole mothers' experiences in the transition from welfare to work. J Sociol. 2002;38(4):345-60.

- Eleveld A. Disrespect or dignity? Experiences of mandatory work participants in the Netherlands from the perspective of the right to work. The Journal of Poverty and Social Justice. 2021;29(2):155-71.

- Fletcher CN, Winter M, Shih AT. Tracking the transition from welfare to work. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare. 2008;35(3):115-32.

- Kissane RJ. They never did me any good: welfare-to work programs from the vantage point of poor women. Humanity & Society. 2008;32(4):336-60.

- Broughton C. Reforming Poor Women: The Cultural Politics and Practices of Welfare Reform. Qualitative Sociology. 2003;26(1):35-51.

- Pearlmutter S, Bartle EE. Supporting the move from welfare to work: What women say. Affilia J Women Soc Work. 2000;15(2):153-72.

- Breitkreuz RS, Williamson DL. The self-sufficiency trap: A critical examination of welfare-to-work. Social Service Review. 2012;86(4):660-89.

- Breitkreuz RS, Williamson DL, Raine KD. Dis-integrated policy: welfare-to-work participants' experiences of integrating paid work and unpaid family work. Community, Work & Family. 2010;13(1):43-69.

- Medley BC, Edelhoch M, Liu Q, Martin LS. Success after welfare: What makes the difference? An ethnographic study of welfare leavers in South Carolina. J Pover. 2005;9(1):45-63.

- Cook K, Raine K, Williamson. The health implications of working for welfare benefits: The experiences of single mothers in Alberta, Canada. 2000.

- Hildebrandt E, Kelber ST. Perceptions of Health and Well-Being Among Women in a Work-Based Welfare Program. Public Health Nurs. 2005;22(6):506-14.

- Behrenz L, Hammarstedt M. Utvärdering av nystartsjobb i Växjö kommun. 2014:16, Linnéuniversitetet.

- Tengland P. The concept of work ability. J Occup Rehabil. 2011;21(2):275-85. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-010-9269-x.

- Brülde B. Folkhälsoarbetets etik: Studentlitteratur AB; 2011 2011-03-17.

- Hägglund P, Johansson P. Sjukskrivningarnas anatomi – en ESO-rapport om drivkrafterna i sjukförsäkringssystemet. Stockholm: Expergruppen för studier i offentlig ekonomi; 2016:2.

- Bergström G, Isaksson M, Petrini E. Ett förebyggande perspektiv på ekonomiskt bistånd. En kunskapsöversikt om insatser som kan motverka eller minska behovet av ekonomiskt bistånd: Göteborgsregionen; 2022.

- Smedslund G. Work Programmes for Welfare Recipients. 2006. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29320088/.

Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services

Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook

Share on LinkedIn

Share on LinkedIn

Share via Email

Share via Email